So, here’s another oddball idea.

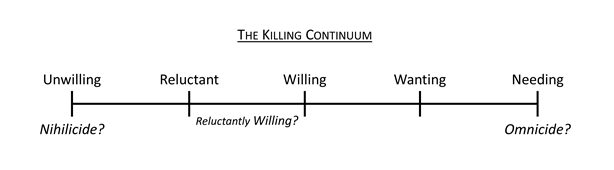

It seems possible to me to illustrate people’s comfort level with deadly force along a continuum, ranging from the unwilling — people for whom taking another human life is completely anathema — to the needing, whose desire to murder their fellow human beings has blossomed into a deep-seated craving, an urge they must satisfy. We might characterize it as being a continuum between “nihilicide” and “omnicide,” between the refusal to kill anyone and the compulsion to kill anyone, if not exactly everyone.

The unwilling, or perhaps the refusers, would not, under any circumstances, pick up a deadly weapon to defend themselves or anyone else. It may be that they would prefer to be killed than to kill. The number of people in this category is probably fairly small, but the best thing about them is that they pose very little threat to anyone else. (Originally I thought they might pose absolutely no threat, but accidents happen, so … no intentional threat, anyway.)

Moving along from there would be people reluctant to apply deadly force, but who recognize that it might be necessary in some circumstances. The idea of killing makes them uneasy, perhaps enough that they would be unlikely to purchase weapons or seek training.

Next would be the willing — those who have thought through the mental process of what it would take to apply deadly force and have become somewhat used to the idea. They might prefer not to, but have steeled themselves to carry it out if need be, and may have gone through some specific training in that regard. I would think most law enforcement and military professionals would fall into this category.

When I posed this question in my newsletter — to which you can subscribe using the form in the top right — a friend suggested that the boundary between the reluctant and the willing might be home to the reluctantly willing. (Perhaps we might consider them the grudging.) They may have had some amount of training, maybe from prior military service or from civilian security or police work, but their willingness to kill may not be quite firm. It might be a matter of caution, or conscience, or uncertainty, or religious conviction; or it might be something they cannot quite articulate. (For the record, this describes my position on the continuum pretty well.)

Moving further along the killing continuum, though, we find more problematic cohorts, beginning with people wanting to kill: people who are not only comfortable with the idea of killing others but who consider it desirable (for whatever reason). The fact that we are not overrun with murderers indicates that this group is relatively small; however, the boundary between this group and the preceding groups can be somewhat porous. Some people may shift into this cohort temporarily, for example, driven by extreme situations, and may occupy it only for a short time (perhaps not even long enough to carry out an attempt).

Beyond them, though, as we approach the omnicide edge, is an even more extreme and far more dangerous cohort: the needing group. Whether it is a matter of obsession, or sadistic pleasure, or devaluation of others, or some other driving force, people in this group intend to kill and may never be satisfied until they have done so. Thankfully, the number of people with such psychopathy is also quite small.

The first question, as stated above, is where do you fall on such a continuum?

The Killing Continuum. Mathematically, it seems the probability of carrying out an attack using deadly force would approach zero on the “nihilicide” end and unity on the “omnicide” end.

Perhaps that continuum is too simple, though. For instance, a friend suggested that it may be possible to add another axis and turn it into a killing matrix, with willingness on the horizontal axis (as above) and some assessment of “rightness” on the vertical axis. The rightness axis might cover a range of attitudes about killing, from its being always wrong up through being right only in certain circumstances (e.g., self-defense, defense of others, preemptive defense) all the way up to seeing homicide as being unequivocally right. On such a matrix, for example, there may be a population of people “willing” to kill who nonetheless believe that homicide is never right. (In the interest of keeping this post from growing out of all proportion, I won’t attempt that expanded version; you are free to work on it as an exercise, though.)

I started thinking about this in terms of whether it may ever be possible to identify people on the increasing-probability end of the continuum — those wanting and even needing to kill. If we could zero in on their intentions and predict their actions, I wonder whether it may be possible to stop them before they succeeded or even to pull them back from the brink, to help them shed the need and the desire to kill before they tried to satisfy it. Another friend pointed out that it probably won’t ever be reliably possible to identify people like that — many of us are able to hide our baser instincts, after all, though most of our baser instincts don’t present threats to our fellows — and that even if we could, we might come to regret the level of totalitarianism that would produce.

So to me the question then becomes, after we consider where we fall on the continuum, whether any manner of societal pressures can prevent a person who wants to kill — or even who thinks they need to kill — from doing so. And, if there are mores and norms and beliefs to counter the urges that lead to such deeds, whether our society has the will to exert such pressures, or even to endorse them.