I’m releasing a new book very soon, a nonfiction volume entitled Elements of War (in fact, I released the e-book version today). I worked on this book on and off for decades: I started it while on active duty in the Air Force (some of its embryonic form was published in the USAF online magazine), and continued after I retired. I originally planned to release it nearly five years ago, but life events interfered.

To adapt an old phrase, I’ve cut bait long enough and it’s time to fish. So by way of introducing the book, I offer this excerpt from chapter twenty-four, “The System of War”:

It may seem odd to categorize war, which is not a discrete thing but rather an abstract notion describing events, as a system … a collection of interrelated and interacting parts that operate together toward a common purpose. A box of odds and ends is not a system; nor is a box of computer components until those components are assembled in working fashion. It seems that such a definition would not describe an abstract notion such as war….

Our purpose is not to apply any single methodology to break down war into its component parts, but to understand more of the whole by using a variety of different methods. By way of analogy, we can compare the art of war to the art of painting. In the case of historical wars, the painting is complete (though we may occasionally encounter a forgery, a reproduction, or a hidden masterpiece); in the case of current wars, it is being painted even now. We evaluate the paintings to determine if they are masterpieces—or if they even qualify as “art.” We must investigate light, shadow, color, and texture to practice our own art, but we need not chemically analyze the paint to learn what makes it burnt umber; instead, we consider the painting as a whole….

For the system of war, the purpose is to achieve victory (i.e., to seize the objective) by force or by the threat of force…. Failure to keep that objective in mind is usually the fault of the political rather than the military machine. Since the mid-1980s the US in particular has searched for “exit strategies” too vigorously, when it should have searched for victory strategies…. We should not be content to stop at a quick military victory unless we are reasonably sure that victory will gain us the long-term, overall victory we really need; however, we cannot know what that overall victory should look like if we have not taken the time to define it and figure out how to achieve it.

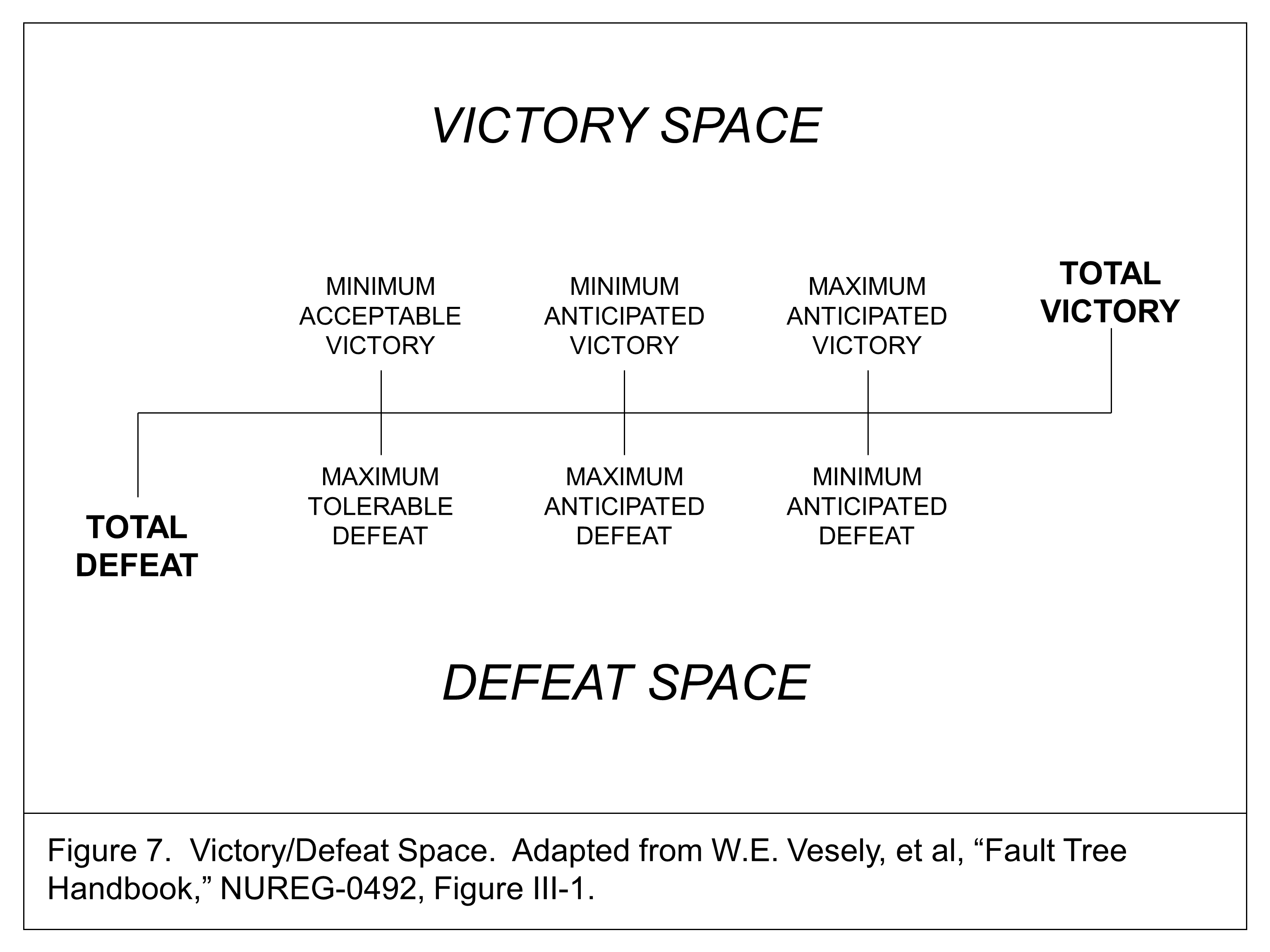

It is important to remember that, “there are degrees of victory, some better than others.” Planners and commanders might consider using the Victory/Defeat Space model shown in Figure 7 to determine the shape of the victory to be sought. By deciding beforehand the definitions for the minimum acceptable victory, the maximum anticipated defeat, etc., decision makers would not only approach any coming war with open eyes but may also be able to discern ways to move from the potential for defeat to the probability of victory. Our definition may, in fact, change as the conflict unfolds. And how we define the victory we want will determine the resources and tactics we need to prosecute the war—no matter what that war may be.

(Victory/Defeat Space. Figure 7 from Elements of War.)

You may have noted that the figure was adapted from a Nuclear Regulatory Commission handbook. That handbook was the text for a system safety and reliability short course I took at the University of Washington in the late 1980s (a temporary duty assignment from my post at Edwards AFB). I don’t recall exactly when I thought of the idea of using the Success/Failure diagram from the text to illustrate different degrees of victory and defeat, but I think it’s an appropriate application — even if it is a bit unusual. (Then again, I seem to have a track record of coming up with unusual things.)

With respect to things going on in the world today, how do you think Russia and Ukraine would define their respective maximum tolerable defeats or maximum anticipated victories? Or, given that China recently deployed forces in military exercises near Taiwan, how would those two countries — and, given our interests, the US as well — define those scenarios to cover an eventual Chinese invasion of the island?

It seems to me that planners and politicians on each side of a conflict would do well to place their different potential outcomes along the continuum, so that even if they cannot achieve total victory they might avoid total defeat.

___

If you think this sort of approach is interesting, or has any value whatsoever — whether in this context, or in the context of negotiations (minimum acceptable salary?), investing (maximum tolerable loss?), or some other aspect of life — I’d be pleased if you would share it with friends! And I’d be even more pleased if you’d pick up the e-book today and/or consider ordering a copy of Elements of War when it becomes available.