Fifty years ago today — May 25, 1961 — President John F. Kennedy spoke to Congress about several national priorities, and laid out the goal of what would become the Apollo program. He said, “Now it is time to take longer strides–time for a great new American enterprise–time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on earth.”

(President Kennedy speaking to Congress. Image from NASA’s history site.)

Speaking close on the heels of Yuri Gagarin’s orbital flight and Alan Shepard’s sub-orbital flight, Kennedy proposed an ambitious agenda in the final major section of his Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs. With emphasis added, and a little commentary interspersed, here’s the text:

… if we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny, the dramatic achievements in space which occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all, as did the Sputnik in 1957, the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, who are attempting to make a determination of which road they should take. Since early in my term, our efforts in space have been under review. With the advice of the Vice President, who is Chairman of the National Space Council, we have examined where we are strong and where we are not, where we may succeed and where we may not. Now it is time to take longer strides–time for a great new American enterprise–time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on earth.

The last sentence of that paragraph is speechwriting gold: a wonderful triplet that wraps up in the appropriately grand idea of the future of all mankind.

I believe we possess all the resources and talents necessary. But the facts of the matter are that we have never made the national decisions or marshalled the national resources required for such leadership. We have never specified long-range goals on an urgent time schedule, or managed our resources and our time so as to insure their fulfillment.

Recognizing the head start obtained by the Soviets with their large rocket engines, which gives them many months of leadtime, and recognizing the likelihood that they will exploit this lead for some time to come in still more impressive successes, we nevertheless are required to make new efforts on our own. For while we cannot guarantee that we shall one day be first, we can guarantee that any failure to make this effort will make us last. We take an additional risk by making it in full view of the world, but as shown by the feat of astronaut Shepard, this very risk enhances our stature when we are successful. But this is not merely a race. Space is open to us now; and our eagerness to share its meaning is not governed by the efforts of others. We go into space because whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share.

Another excellent phrase: “whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share.”

I therefore ask the Congress, above and beyond the increases I have earlier requested for space activities, to provide the funds which are needed to meet the following national goals:

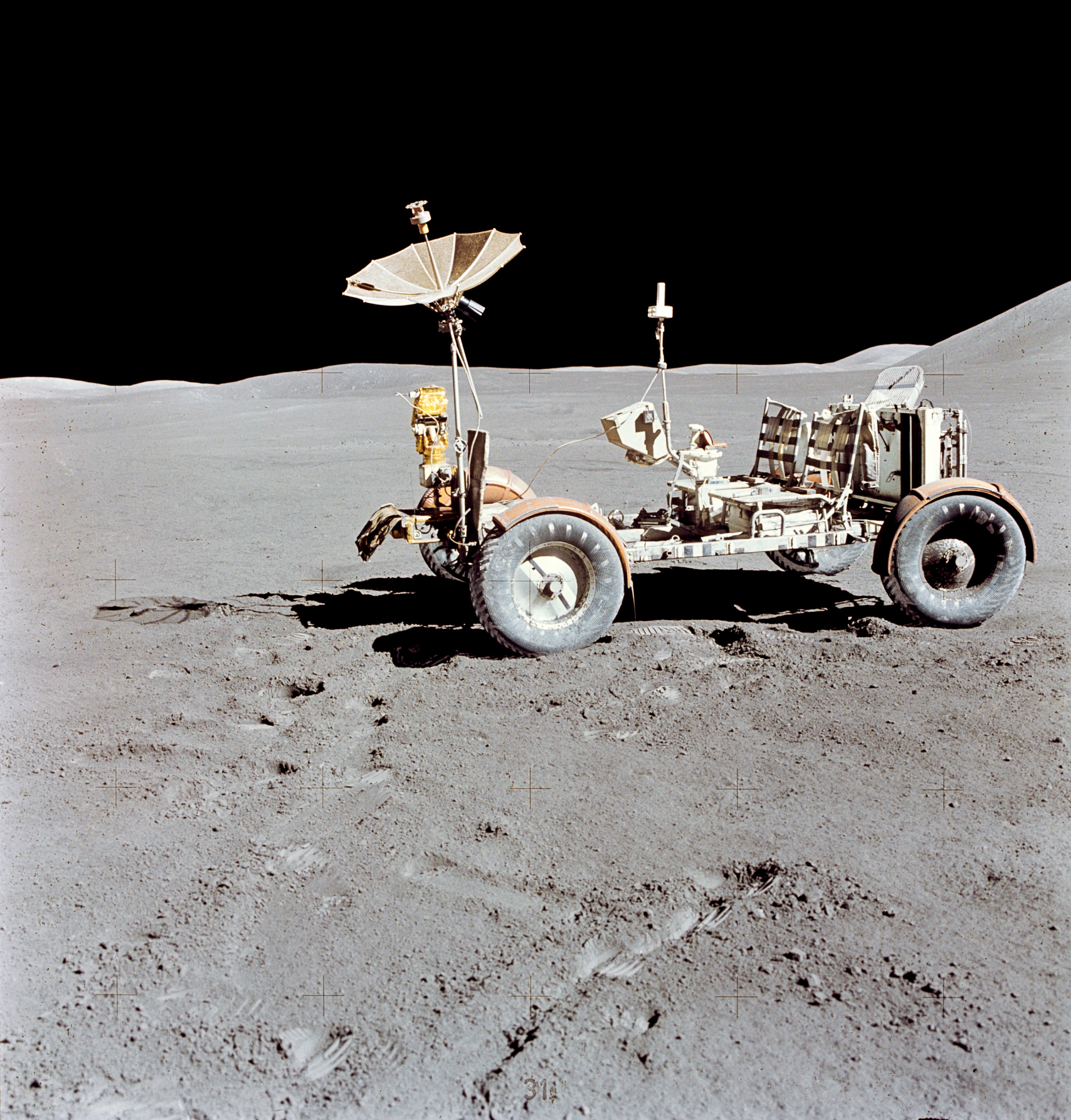

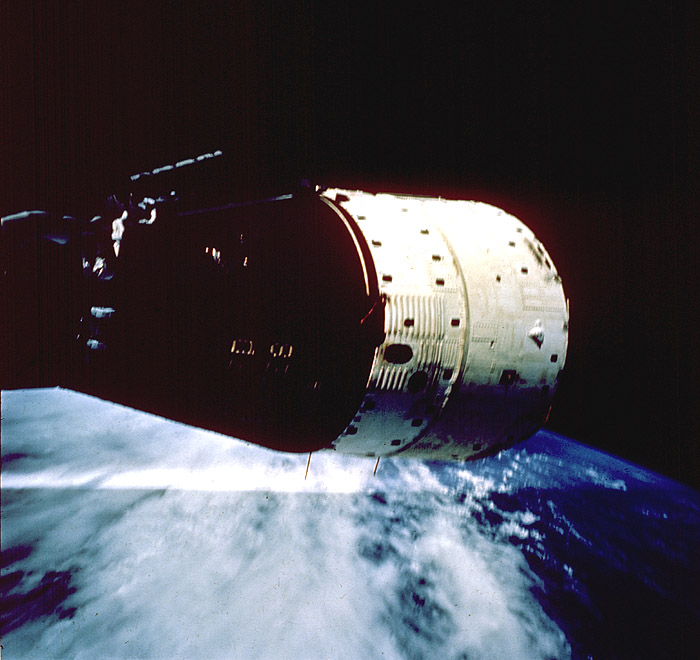

First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. We propose to accelerate the development of the appropriate lunar space craft. We propose to develop alternate liquid and solid fuel boosters, much larger than any now being developed, until certain which is superior. We propose additional funds for other engine development and for unmanned explorations–explorations which are particularly important for one purpose which this nation will never overlook: the survival of the man who first makes this daring flight. But in a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon–if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.

Kennedy masterfully pulls the entire nation together into this grand enterprise. He will repeat the idea later, in a more direct way. First, some specifics …

Secondly, an additional 23 million dollars, together with 7 million dollars already available, will accelerate development of the Rover nuclear rocket. This gives promise of some day providing a means for even more exciting and ambitious exploration of space, perhaps beyond the moon, perhaps to the very end of the solar system itself.

Think how far out we might have space outposts if we had nuclear rockets. If you’re less optimistic, you might think about accidents with nuclear rockets; but still, nuclear propulsion would take us farther than chemical rockets ever will.

Third, an additional 50 million dollars will make the most of our present leadership, by accelerating the use of space satellites for world-wide communications.

Fourth, an additional 75 million dollars–of which 53 million dollars is for the Weather Bureau–will help give us at the earliest possible time a satellite system for world-wide weather observation.

Let it be clear–and this is a judgment which the Members of the Congress must finally make–let it be clear that I am asking the Congress and the country to accept a firm commitment to a new course of action, a course which will last for many years and carry very heavy costs: 531 million dollars in fiscal ’62–an estimated seven to nine billion dollars additional over the next five years. If we are to go only half way, or reduce our sights in the face of difficulty, in my judgment it would be better not to go at all.

No doubt, then as now, many people believed it would be better not to go at all. I, obviously, am not one of them. I like the way he lays it out as a challenge, though: in effect advising Congress to go “all in” long before poker became a popular spectator game.

Now this is a choice which this country must make, and I am confident that under the leadership of the Space Committees of the Congress, and the Appropriating Committees, that you will consider the matter carefully.

It is a most important decision that we make as a nation. But all of you have lived through the last four years and have seen the significance of space and the adventures in space, and no one can predict with certainty what the ultimate meaning will be of mastery of space.

I believe we should go to the moon. But I think every citizen of this country as well as the Members of the Congress should consider the matter carefully in making their judgment, to which we have given attention over many weeks and months, because it is a heavy burden, and there is no sense in agreeing or desiring that the United States take an affirmative position in outer space, unless we are prepared to do the work and bear the burdens to make it successful. If we are not, we should decide today and this year.

This decision demands a major national commitment of scientific and technical manpower, materiel and facilities, and the possibility of their diversion from other important activities where they are already thinly spread. It means a degree of dedication, organization and discipline which have not always characterized our research and development efforts. It means we cannot afford undue work stoppages, inflated costs of material or talent, wasteful interagency rivalries, or a high turnover of key personnel.

New objectives and new money cannot solve these problems. They could in fact, aggravate them further–unless every scientist, every engineer, every serviceman, every technician, contractor, and civil servant gives his personal pledge that this nation will move forward, with the full speed of freedom, in the exciting adventure of space.

Once again, Kennedy issues the call not only to Congress but to everyone who is likely to be involved in the effort. “This nation will move forward, with the full speed of freedom, in the exciting adventure of space.”

All in all, a brilliant speech — and the rest, as is so often said, is history.

The quest for the Moon had begun.

___

Author’s Note: This is the 2nd attempt to make this post; the first attempt this morning appeared to work but then encountered a technical error.

by

by