In other blog posts, I’ve catalogued the Space Shuttle landings I worked as part of the AF Flight Test Center team at Edwards AFB — I worked four landings, and saw quite a few more — and with that experience in mind I watched with proud sorrow the shuttle Atlantis glide in for its landing this morning at the Kennedy Space Center.

When the shuttle era began, we had high hopes for it, and though it was exciting to be even a small part of it the program never lived up to our expectations. But as we close the books on this phase of the U.S. space program, and especially as we look forward with hopeful anticipation to some new phase, let’s not forget to look back as well to the pioneers who braved the hazards of the earliest days of space exploration.

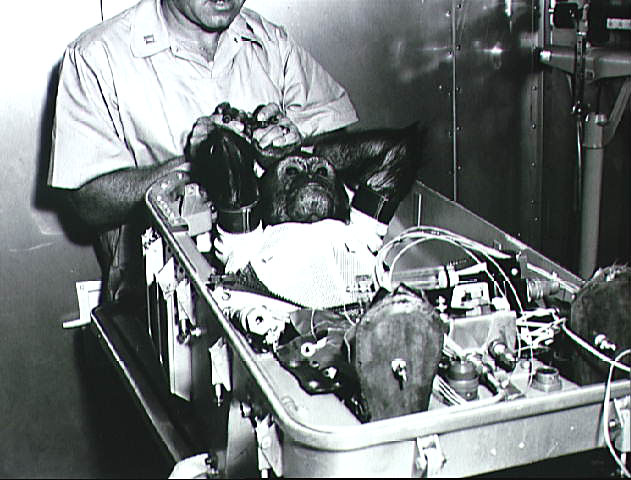

Because 50 years ago today — July 21, 1961 — Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom became the second U.S. man in space. His Liberty Bell 7 capsule launched into a suborbital trajectory atop a Redstone rocket, in a mission appropriately labeled Mercury-Redstone-4.

(View of earth from Mercury-Redstone-4. NASA image.)

The MR-4 capsule differed from Alan Shepard’s “Freedom-7” capsule in that it had an enlarged window and a new type of hatch:

The explosively actuated side hatch was used for the first time on the MR-4 flight. The mechanically operated side hatch on the MR-3 spacecraft was in the same location and of the same size but was considerably heavier (69 pounds rather than 23 pounds). The explosively actuated hatch utilizes an explosive charge to fracture the attaching bolts and thus separate the hatch from the spacecraft. Seventy 1/4-inch titanium bolts secure the hatch to the doorsill. A 0.06-inch diameter hole is drilled in each bolt to provide a weak point. A mild detonating fuse (MDF) is installed in a channel between an inner and outer seal around the periphery of the hatch. When the MDF is ignited, the resulting gas pressure between the inner and outer seal causes the bolts to fail in tension. The MDF is ignited by a manually operated igniter that requires an actuation force of around 5 pounds, after the removal of a safety pin. The igniter can be operated externally by an attached lanyard, in which case a force of at least 40 pounds is required in order to shear the safety pin.

However, “After splash-down, the explosive hatch activated prematurely while Grissom awaited helicopter pickup.” The capsule sank, but was ultimately recovered from its 15,000-foot-deep resting place.

Liberty Bell 7 was finally raised from its resting place on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, some 4.8 km below the surface and 830 km northwest of Grand Grand Turk Island, in 1999 after a number of expeditions. Two expeditions to the area, in 1992 and 1993, were unsuccessful in locating the capsule. The next expedition succeeded in locating the capsule on May 2, 1999, but the cable which linked the surface ship to the submersible (which would have towed the capsule to the surface) broke, resulting in the loss of the submersible and temporarily dashing the hopes of those who intended to retrieve a piece of history. A final expedition, to recover both the submersible and the capsule, succeeded on July 20, 1999, in raising the capsule to the surface. Still attached to the capsule was the recovery line from the helicopter which tried to save it from going under in 1961. Also among the artifacts found inside were some of Grissom’s gear and some Mercury dimes which had been taken into space as souvenirs.

Grissom, about whom you can read more in this expanded NASA biography, traveled into space once more, as commander of the first Gemini mission, and died in the Apollo-1 launch pad fire.

It seems somehow poignant for the last Space Shuttle to return to earth on the 50th anniversary of the first spaceflight of one of our country’s space pioneers.

May the time come soon when the U.S. once again launches our brave pioneers into orbit … and beyond.

by

by