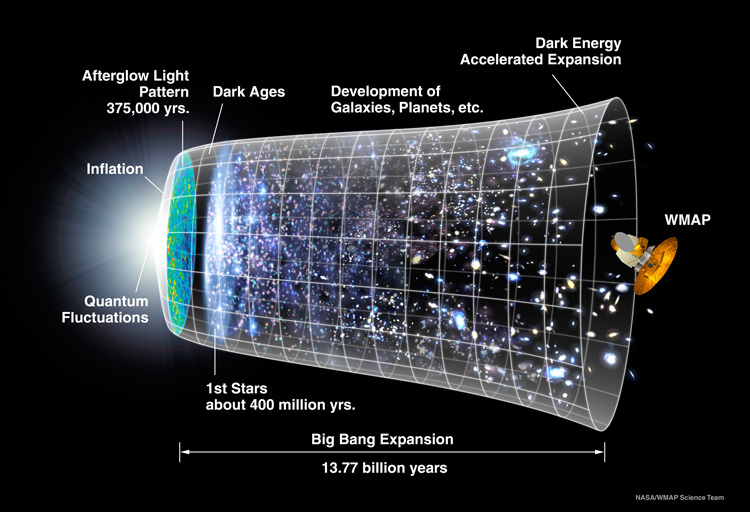

Ten years ago today — June 30, 2001 — a Delta-II rocket out of Cape Canaveral launched a mission to study the mysteries of the very early universe.

(A graphical representation of the growth of the universe, with WMAP at the far right. NASA image.)

The Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, or WMAP, was originally simply the MAP — it was renamed in February 2003 after cosmologist David T. Wilkinson.

In August 2001, WMAP arrived at the L2 LaGrange point, a quasi-stable point on the other side of the Earth from the Sun, about five times farther away from the Earth than the Moon. WMAP operated in a halo orbit around the L2 point, scanning the sky over its 7-year operational life.

Among its other accomplishments, WMAP mapped the cosmic microwave background radiation from the early universe, and produced data to determine that the universe is about 13.73 billion years old (plus or minus 120 million years). Its other findings are catalogued on this WMAP page, which also includes quotes from leading researchers.