(To read the first entry in this occasional series, see Unprepared for Regret.)

Valentine’s Day is special for many couples, but for my wife Jill and me it was particularly noteworthy because it marked the beginning of our serious relationship.

We had met in the Fall of 1979, when I was a sophomore and she was a freshman at Winyah High School in Georgetown, SC. She and her friend Evelyn were equipment managers for the football team, and I first met them when I stood at the counter to get my shoulder pads and helmet. It was the closest I’ve come to “love at first sight,” but she didn’t have quite the same reaction.

In the Spring of 1980, we ran track together. I first held her hand on one of the bus rides home from a meet, and I used to stand on the infield and “catch” her when she finished her races. I came to like her very much — truth to tell, I fell in love with her very quickly — and she liked me, too … but not too much later she told me she only wanted to be friends.

With Jill on the front steps of Winyah High School in the Spring of 1980 — before she told me she just wanted to be friends.

By the Fall of 1981, we were still friends. We had both had other relationships that hadn’t worked out, and I had seen her once over the summer and jokingly told her that if five years went by and neither of us married anyone then we should just marry each other. I think she laughed at the idea … but I don’t have much memory for the details of events in my life, so I can’t be sure. Anyway, that Fall Jill agreed to let me sponsor her for Homecoming, and to take her to a Halloween party and a football awards banquet, but we were not “dating” in any serious sense.

And then came Valentine’s Day of 1982.

We both went separately to the dance in the high school gymnasium, and late in the evening I asked her to dance a slow dance with me. I was never a very good dancer, but Jill was — I was always intimidated when dancing with her, and might not have had the courage to ask her if I hadn’t been just a little bit drunk (and, yes, I admit that I was a few months shy of the then-legal age of 18).

During that slow dance, possibly fueled by that same liquid courage, I said something along the lines of, “I know you don’t want to hear this, but I think I will always love you.”

And, to my surprise and delight, Jill said she loved me, too.

I feel certain that we kissed, and I wish I could remember it. A short time later, she had to catch a ride with her friends back to her house, and I recall being a bit unsure that she had really said she loved me. I had wanted to hear her say it for so long, I couldn’t quite believe it was real. But it was.

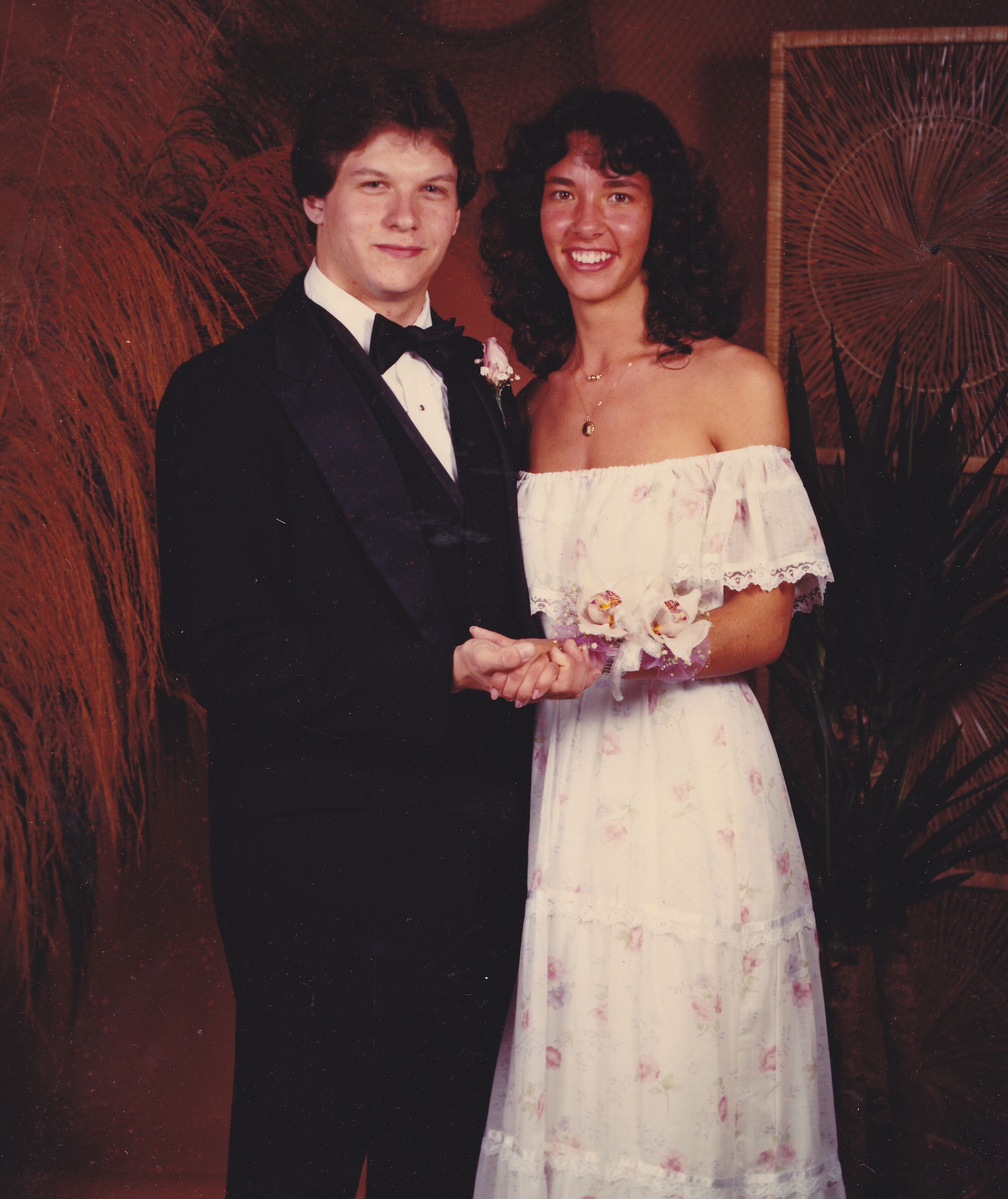

Ten weeks later we went to my Senior Prom together.

With Jill at my Senior Prom in May 1982.

We were married three years after that. We had some ups and downs, before and during, but our marriage lasted 34 years and change — and every Valentine’s Day was special because they marked the first time we both admitted (or, agreed) that we loved one another.

___

Postscript:

About two months after Jill died, I went home to Georgetown and walked our puppy around some of our old haunts. At one point I stood in front of the old, run-down, tawdry gym and thought about that Valentine’s dance. I wished for a clearer memory of that night — of the song we danced to, of what she wore, of the smell of her perfume, of her face in the low light — but my brain is built to remember what happened more than how it happened.

That defect in my memory — that it is “declarative” rather than “episodic” — is something I deeply regret, something I was unprepared to deal with in terms of grief, and something I dearly wish I could overcome — because I want to remember Jill more clearly, and to recall more vividly the good times we had. But I can’t … and as a result my life without her is sadder and more empty than it might otherwise be.