(Cross-posted, with some light edits, from my 12 June 2018 guest post on the Speculative Faith blog.)

The conventional wisdom is that authors shouldn’t read reviews of our own work.

If the reviews are good, they can inflate already outsized egos, and if the reviews are bad, well — egos don’t always just deflate. A hot-air-balloon-sized ego, pierced by a bad review, might slowly settle into a mass of hard-to-wrangle canvas, but a smaller, more fragile ego might burst into shreds that are impossible to reassemble.

Nevertheless, some of us are drawn to reviews like moths to flame. If we’re lucky, the flame is a gentle candle and we just get singed if we get too close. If we’re unlucky, it’s a napalm-spewing flamethrower and we get terribly burned.

Sometimes we just get confused, as I was at two contrasting reviews of my novel, Walking on the Sea of Clouds. First, an Amazon reviewer gave the novel three stars and noted that it was a “good story” with strong character development but was “a bit bible-preachy [sic] for [their] tastes in hard science fiction.” Then the first issue of the Lorehaven online magazine included a brief, positive review that warned those seeking discernment that the story “only briefly referenced Christianity.”

Same story. Bible-preachy. Only briefly referenced Christianity.

I think this illustrates the fact that every reader brings their own experiences, attitudes, and expectations to the stories they read. Orson Scott Card told us in his writing workshop that whatever we’ve written is not the story, because the real story is in the reader’s head — and what’s in your head when you read a story is different from what’s in another person’s head when they read the same story. You might agree on some points, but you’ll disagree on others, and that’s okay.

In the case of my novel, someone who was not used to reading about believers and faith in the context of hard science fiction was put off by it. I have no way to know whether that person is a believer who was just surprised or a nonbeliever who was repulsed, and that really doesn’t matter. Their reading of the text is just as valid as anyone else’s — including the Lorehaven reviewer who might have been looking for more overt Christian themes. Was that person disappointed not to find them, or just surprised? I have no way of knowing, and again it hardly matters because however they read the story was the right way, for them.

Same story. Different readers. Different results.

It reminds me of what the Apostle Paul wrote to the church at Corinth, about the message of the cross seeming foolish to the lost, but representing the very power of God to those of us who believe (1 Corinthians 1:18). Same message. Different audience. Vastly different results.

Even within the body of believers, though, we can differ in our interpretations of Scripture. How much more should we expect to differ in reading science fiction and fantasy stories?

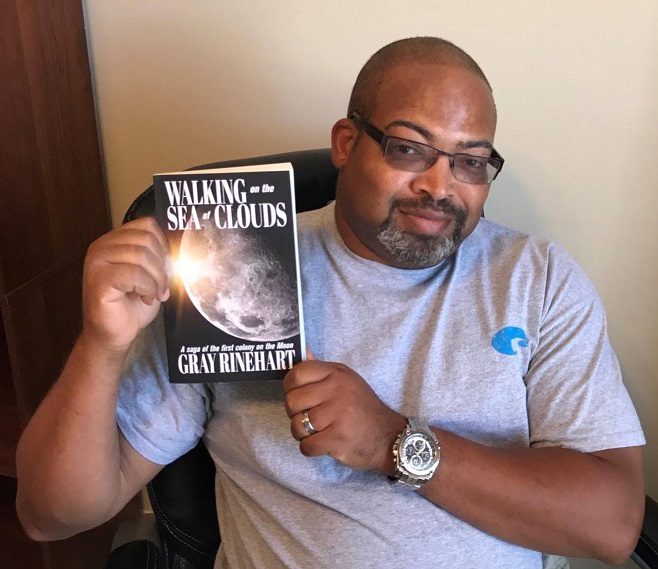

My friend Keith Phillips (Colonel, USAF, Retired), with whom I served in the 4th Space Operations Squadron, showing off his copy of Walking on the Sea of Clouds.

What does it take to cross the spiritual divide effectively in a literary or artistic work? Is it foolish even to try? I hope not, because in this age of growing doubt and disbelief I believe that Christian ideals, values, and themes still have a place in literature and art, whether science fiction, fantasy, or more mundane creations. And not just Christian principles, but Christian characters belong in fantastical stories — even in technology-heavy hard science fiction — just as surely as Christian people belong in every profession.

Unfortunately, sometimes the Christian characters in these stories end up being caricatures more than characters, reflecting the authors’ preconceptions rather than being portrayed as individuals, as people. I’ve found this to be true in stories by believers and nonbelievers alike, and it was something I tried to avoid.

That is, I tried to cross the spiritual divide by including Christian characters where they’re not always found — and by representing them as individual people with their own virtues and flaws, and even with different attitudes toward and expressions of faith. Some talk about it, some hide it, some deny it. Some ignore it, some sneer at it, some question it. That seemed realistic to me, and above all I tried to make the story seem realistic.

And maybe those two contrasting reviews — too much Bible to some people, not that much to others — show that I struck the right balance after all.

If you’ve read the story, I’d love to know what you think! And if you haven’t read the story, then now you know a little more of what you might find in it.

by

by