(Another entry in our continuing series of quotes to start the week.)

I thought of this week’s quote when I read business coach Chris Brogan’s newsletter, which I highly recommend if you’re trying to improve your connections with your customers.* On Sunday his newsletter focused on decision making, and it reminded me of a great quote I read years ago in Go Rin No Sho (A Book of Five Rings) by Miyamoto Musashi:

You must train day and night to make quick decisions.

I used that quote frequently when I was in the service, especially when I counseled the folks who worked for me on my expectations and their performance. As you might expect, decision-making was a key topic — the Air Force evaluation form had a specific section for us to cover “Judgment and Decisions.” And often the decisions we had to make were time-critical; for example, my own decisions about how to control and clean up rocket propellant spills and fires, or about diagnosing and repairing satellite ground systems to restore strategic communications.

I told my officer and enlisted Airmen that when they started to feel paralyzed by a decision in front of them they should concentrate on making the right decision more than on making a good one. I explained that a decision is neither good nor bad at the time you make it, because the outcomes are still unknown: at the time we make a decision, it can only be either right or wrong.

That is, every decision is based on the situation as we know it, and in the case of crisis situations in which quick decisions must be made we almost never have complete information. But every decision is also inherently a prediction of what is likely to happen, and our predictions (sad to say) are subject to error.

A decision may be correct — the appropriate response to all the factors we’ve got in mind — yet still yield a negative outcome. Only after we’ve made the decision and have experienced the consequences can we make a value judgment of whether the decision was good or bad.

The right decision may turn out bad for any number of reasons — we may have missed some key factor, external influences may have come into play that were beyond our reckoning, etc. — but the possibility of a bad outcome should not paralyze us if we know what the right decision is in that moment. The fact that right decisions may have bad outcomes (and vice-versa, though it’s less likely) is part of the basic irrationality of the world; i.e., why the world, in some respects, fails to make sense.

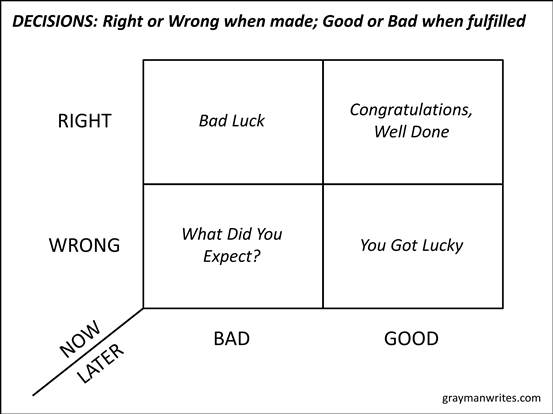

Here I’ve tried to illustrate that when we make a decision — NOW — it’s either right or wrong, but whether the decision turns out to be good or bad is determined LATER. In my experience, it is unlikely for the wrong decision — one that is incorrect or inappropriate for some reason — to yield a good outcome, but it is at least possible.

If social media is any indication, many second-guessers don’t seem to recognize this temporal element to decision-making. Hindsight — that wonderful tendency to look in the rearview mirror of life and see how things might be different (strong emphasis on “might”) if only a different decision had been made — is only 20/20 because often our glasses are tinted. Whether rose-colored or some other shade, through those glasses we never see things as they really were, but only as we imagine they were, colored by all we know now. (Robert Frost was right about the saddest words in the world: “it might have been.”)

As an aside, this also makes me ponder the limits of machine decision-making. Will computer science get to the point that machines can formulate criteria on which to base a decision (knowns and possible unknowns, risks and rewards, potential outcomes, etc.); prioritize and weigh those criteria; evaluate the given situation according to the criteria; and then make a decision, observe the outcomes, and make a value judgment on the effectiveness of the decision? How many “do-loops” and “if-then” interactions do we go through with every single decision we make — even the trivial decisions, let alone the really important and sometimes time-critical ones? In our efforts to make a machine consciousness, will we be able to program those complex, dynamic processes into a machine? And since much of our decision-making operates outside of rational, conscious thought, will a machine’s unconscious (or, even, subconscious) processes ever develop to the point that it will not freeze when faced with a new situation requiring even a simple decision? This is partly why I’ve told panel audiences for years that I think the search for artificial “intelligence” is a bit mistaken. I maintain that artificial “knowledge” is necessary, in the full sense of theory of knowledge, for any machine intelligence to approach our own — and that is a much higher bar to clear.

But for now, when you are faced with decisions this week, I hope you’ll trust yourself to make the right ones, and that in so doing you will help train yourself to make quick decisions when they’re really necessary. The question of whether those decisions are good or bad will have to wait until you know all the consequences — but in my estimation making the right decision should make a good decision more likely.

___

*If you’ve spent much time on the Internet the last few years, you’ve probably heard of Chris Brogan — he’s only written a half-dozen or more bestselling books and built an extensive social media empire. If you want more information about him, check out his Owner Media Group, where you can sign up for his newsletter. (Or for something completely different you can sign up for my newsletter at this link.)