I ran for elective office this year, and lost. (For the record, I spent about 0.41% of the total that all four candidates in my district spent up until the election, and I got 3.5% of the vote. Not close to winning, but a good return on my meager investment.)

I was also nominated for a Hugo Award this year, and lost. The story behind that has been chronicled on this blog and elsewhere, and I won’t go into it in this post. (For the record, and as nearly as I can tell from trying to figure out the preferential voting numbers, about 9% of the 5100 novelette voters selected my story as their first choice. I ended up in fourth place . . . two spots below “No Award.”)

I introduce the fact of my being on political and literary ballots this year because I observed two things in the recent Town Council election process that seem pertinent to this year’s Hugo Awards. Specifically, that the political parties inserted themselves deeply into what was supposed to be a nonpartisan race, and other players also wielded considerable influence; and that a lot of voter information was readily available for the candidates to use.

Now, with the caveat that this post is very long, I’ll try to make those connections.

Parties, Power Brokers, and Influence. I ran for Town Council in a single district here in Cary, North Carolina, and though the race was ostensibly nonpartisan the parties definitely made their presence known. The Republican Party endorsed one of the three of us who identified as Republicans — though not this particular candidate — and the Democratic Party endorsed the fourth candidate. The party endorsements brought with them not only some cachet, which those two candidates used to their advantage, but also party money for advertising as well as organized volunteer efforts for canvassing neighborhoods and working the polls.

In addition to the parties, several civic and professional groups were quite interested in the campaign. Some invited the candidates to meet with them in interviews or to fill out interview questionnaires; some sponsored “meet the candidate” social events; some even sponsored debates between the candidates. A few of those groups also endorsed candidates — again, not this candidate — and encouraged their members to support that person who they felt most confident would represent their interests if elected.

What relation does this have to the Hugo Awards? Simply, fandom has developed its own “parties” and thus the Hugo Awards have their own sets of power brokers (or would-be power brokers).

This year some people were very open about exercising their power. The “Sad Puppies” campaign was a party of sorts and encouraged people to consider specific works (mine included), while the follow-on (and aptly named) “Rabid Puppies” campaign flatly admitted that they intended to wield whatever power they could. When they succeeded at placing their preferred stories and people on the ballot — beyond my wildest imagining, if not others’ — a less organized but much more vocal cohort coalesced to wrest the voting power back into the hands of long-time WorldCon members (i.e., the traditional Hugo nominating-and-voting fans).

That is not to say that Hugo Award power brokers have only been active in recent years. Key figures in the science fiction and fantasy industry have long enjoyed considerable influence within the relatively small community of WorldCon fandom. Whether by their positions in publishing houses or the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA), their notoriety, or the force of their personality; whether by their knowledge of the field, their literary achievements, or the number of people who read their blogs; or whether by other factors entirely, clearly some people became movers and shakers in fandom, and perhaps even kingmakers in terms of placing their favored selections on the Hugo ballot.

There was, for instance, considerable electronic weeping and wailing this year over whether, in the past, some “cabal” of industry insiders exercised deliberate and coordinated control over the nominating process. Accusations were levied with no proof beyond some statistical correlations, and despite the relatively weak charges they were at times denied with enough stridence that the old phrase “the hit dog howls” came to mind.* But from a group dynamics standpoint, a cabal was never necessary in order for insiders to have influence over the process. In the same way that a CEO or other leader can forget how much power they have over their employees and followers, people with informal power can forget that even a casual suggestion or question — “Have you read the new novel by [beloved author]? It’s marvelous” — can have an outsized effect on those who hear it.

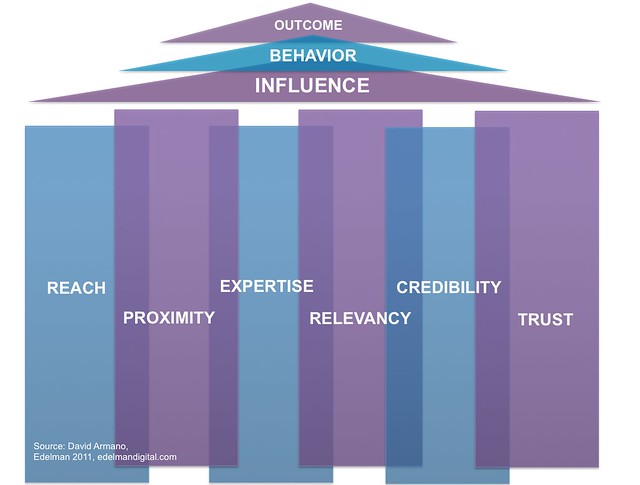

People can exert influence accidentally as well as intentionally. (Image: “Pillars of Influence,” by David Armano, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

Taking that a step further, people can in some ways grow comfortable with or even addicted to the power they wield, even if that power is informal. They can come to enjoy it, to depend on it, and therefore to resent when it seems to have been taken away from them. In response, they could resort to making veiled (or not so veiled) threats, or to levying personal accusations that are demonstrably untrue. Again, the hit dog howls.

I will say at this point that I doubt there ever was a super-secret cabal directing Hugo-related fandom. But I know for a fact that insider politicking is as real in SF&F as it is in electoral politics, because I was faced with it in mid-April. Shortly after the nominations were announced, a friend of mine who has won Hugo and other awards and is generally well-known in SFWA and the SF&F community approached me, unsolicited and unexpectedly, to encourage me to withdraw my story from consideration.**

My friend wrote,

I think that you are a talented writer and that this is not going to be your only good story. . . . I think that if you made a statement withdrawing your story from the ballot, that you would get a bump next year and land on the ballot again. Not guaranteed, but I think that you would get a lot of good will.

My friend rightly pointed out that in some ways my nomination made me a pawn, a human shield, in the great Hugo fracas. My friend somewhat glossed over the point that I was destined to end up in someone’s bad graces no matter whether I let my nomination stand or withdrew it, but my friend was unceasingly gracious and pledged to support me no matter which decision I made. I very much appreciate that friend’s concern and their willingness to share their point of view while respecting mine; I count myself fortunate to have such a friend.

Now, a concerned friend reaching out like that would not by itself constitute insider politicking, even when the friend is nearly as deep inside the SF&F community as is possible to go. But when that same friend sends pretty much the same message to other nominees (a fact I verified from other people contacted), then . . . well, it certainly seemed to fit the description of a relatively powerful insider trying to exert influence over the process.

When one of the other nominees asked my friend about the fact that they had approached several of us, my friend wrote,

I was talking with a bunch of you individually . . . and started cutting and pasting from one email to the other. . . . I should have thought of how that would look. Please convey my apologies to whoever you spoke with.

I give my friend the benefit of the doubt, but I saw much the same thing even in the little Town Council race: insiders and special interests approaching candidates to see if we agreed with them or could be swayed to their positions. Some were more open and obvious about it than others, and their motives were clearer. As for my friend, I believe they were genuinely concerned for me and the other friends they contacted, and concerned for what the schism appeared to be doing to the community of fandom.

Looking back at what my friend proposed, it seems somewhat ironic to think that by withdrawing after being nominated I might improve my chances of being nominated in the future, not because anything else I might publish would be better than my 2015 nominated story, but because I would have engendered “good will” with the traditional fan contingent. As I wrote in reply,

. . . from a pragmatic standpoint I’m not sure whether withdrawing would really earn me the good will you speak of. I hope it might. But if good will garnered in that fashion is more important than any qualities inherent in my work . . . then the award really is more than just literary.

Consider this: If some of those who did withdraw — such as my friends Annie Bellet and Edmund Schubert — are nominated in the future, will they wonder if factors besides literary merit influenced the outcome? Since the primary complaint against my story and others was that they were nominated for reasons having little to do with their relative merits, it’s hard to see much of a difference with regards to receiving a friendly “bump” to “land on the ballot again.”

But in addition to the influence (deliberate or incidental) of insiders and power brokers, the other thing I observed in electoral politics that has some bearing on the recent Hugo unpleasantness is

A Plethora of Voter Information. Very early in my run for Town Council, I learned that the Wake County Board of Elections had available a comprehensive database of registered voters. I downloaded it as a huge Excel spreadsheet and narrowed it down first to Cary and then to just my district. In the end, I still had a lengthy list of around 24,000 registered voters that included names, addresses, party affiliations and other information, up to and including whether (and by what method) they voted in recent elections. The only thing missing was exactly for whom they voted.

How does that relate to the Hugo Awards?

During the WorldCon business meeting, when changes to the nomination-and-voting procedures were being proposed and debated, the membership passed a resolution calling for the convention organizers to release anonymized nomination data. The convention committee agreed to do so, but shortly thereafter appeared to back away from fulfilling that agreement because, as I understand it, they were finding it too difficult to produce the data without giving away the identifying information.

Why would the nomination data be interesting?

Consider that, within hours of the Hugo Awards ceremony closing, the io9 blog published an article with the title “This Is What The 2015 Hugo Ballot Should Have Been” in which the author put forth a vision of what the award results might have been had the “Sad Puppies” and “Rabid Puppies” entries not been nominated. The author began with this:

Based on the newly released statistics, Brandon Kempner of Chaos Horizon has a good analysis of the Hugo vote, (as does Nicholas Whyte in From the Heart Of Europe)—they estimate that the Rabid Puppies bloc was composed of 550-525 voters, while the Sad Puppies bloc made up 500-400 voters: around 20% of the 5,950 total voters. Of those numbers, around 3500 likely voted “No Award” out of principle, objecting to the lockstep nomination process of the Puppies.

and then made the leap from the number of voters to the idea that the SP/RP entries might not have been nominated at all. To me (the former engineer and nonstatistician), that seems to be trying to produce orange juice from a bag of apples. The question of what would have been nominated requires delving into the nomination statistics; the voting statistics are irrelevant to that question, because it turns on how many SP/RP nominations there were, not how many votes there were after months of competing rhetoric. With only the raw nomination figures, i.e., without the data that would provide insight into nomination patterns, it seems unsupportable to conclude that none of the stories and people on the SP/RP lists would have been nominated.***

Returning to the example of voter rolls that do not reveal voting results, it seems reasonable to imagine that if the Board of Elections can record votes and yet produce a database of registered voters that contains everything but those voting results, then it should be a simple enough — or certainly no more complicated — database management task for the WorldCon committee to produce records of the Hugo nominations without including identifying information, whether name or membership number or IP address.

Along those lines, if the WorldCon committee’s IT experts — and it’s a committee of geeks, surely they have ready access to a number of technology, computing, and database experts — cannot find a way to produce the promised data, then perhaps they could turn to the local Board of Elections for assistance. I doubt my local Board of Elections is that much different from any other in the country; it seems that their local board in Spokane should be able to provide some guidance.

Conclusion: Heinlein May Be Right.

Robert A. Heinlein maintained in Double Star that “Politics is the only sport for grownups — all other games are for kids.” As someone who enjoys other games and sports, as a spectator and participant, I’m not so sure about that; maybe I haven’t “put away childish things” in that respect, but I’m generally in favor of practicing youthful exuberance in order to stay young at heart. So I suggest a corollary to RAH’s observation: Politics is the sport people play even when they don’t intend to.

All human organizations, from churches to businesses to science fiction and fantasy conventions, are suffused with politics, some of it practiced openly and some of it practiced surreptitiously. It would be disingenuous to claim that the Hugo Awards were ever without politics and politicking; indeed, during the run-up to this year’s awards many thoughtful commentators acknowledged the awards’ political past, though the degree to which politics overshadowed this year’s award was unprecedented.

Perhaps I’m uncomfortable with Heinlein’s assertion because I obviously have not played the political game well, but I’d like to suggest that another of his observations may be more apt, more relevant as we move forward. From Friday: “It is a bad sign when the people of a country stop identifying themselves with the country and start identifying with a group. A racial group. Or a religion. Or a language. Anything, as long as it isn’t the whole population.”

We continue to see this play out in electoral politics, as small groups band together in solidarity over their specific interests. And we’ve seen it in genre politics as well, whether the rallying cry is “Diversity Now!” or “Golden Age Forever!” or something equally narrow in scope. The implication is that the way we think about the subject is right and all other ways must be wrong, which is a peculiarly limiting viewpoint in a community that enjoys speculating about all manner of fantastic encounters and possible futures.

From my perspective it seems that part of the issue from the beginning of this year’s Hugo Awards melee was a difference in outlook among people who love genre fiction in all its forms, but who placed themselves in one of two groups: one that loves genre and also loves fandom itself, and considers fandom the ultimate expression of its love for the genre; and another that loves genre but for which fandom and the fan community is an adjunct, an addendum, rather than a critical component of their genre experience. That is, one group was devoted to fandom as well as genre; the other was devoted to genre but not (or less) to fandom.

And as long as we divide ourselves, or in the case of fandom subdivide ourselves; as long as we separate ourselves into (virtual or actual) walled-off enclaves and echo chambers, and associate only with those who look like us, act like us, and believe the things we do; we will find it harder to understand, relate to, and get along with one another — in civil life as well as in the SF&F community.

I think we would be well-served as a fannish community if we talked more about what we love and why we love it, without implying that those who do not love it as we do are ignorant or contemptible. And I think we would be better off if we recalled another RAH observation, also from Friday (emphasis in original): “Sick cultures show a complex of symptoms . . . but a dying culture invariably exhibits personal rudeness. Bad manners. Lack of consideration for others in minor matters. A loss of politeness, of gentle manners, is more significant than is a riot.” I believe the pithy advice that bears ST:TNG alumnus Wil Wheaton’s name sums that up rather well.****

I had several e-mail exchanges with the friend who encouraged me to withdraw my nomination, and my friend helped me refine this statement of what I would like to see in our discourse: I’d like to have less shouting and more talking; less gloating, more humility; less blaming, more acknowledgement of different points of view; less name-calling, more self-deprecation; less rage (but no less passion), more acceptance.

It is possible to disagree without being disagreeable; if it were not, I would have far fewer friends in this field. It may not be easy, but it is possible — and if Heinlein is right, it is actually necessary if the community (whether the SF&F community or the larger polis) is to survive.

I hope, for my part, I have succeeded in doing so. But that is for others to judge.

___

*If you prefer something more eloquent, perhaps “doth protest too much” would fit the bill.

**I do not intend to identify the person, because I do not want them to face any recriminations; I realize that makes some of the usage here awkward. If my friend wants to self-identify, that’s up to them.

***For example, I perused the 2015 Hugo Award Statistics and it appeared to me that both Annie Bellet’s “Goodnight Stars” and Kary English’s “Totaled” might well have been nominated even if they had not appeared on an anathema list. If that’s true, I’m not sure whether that would make their Annie’s subsequent withdrawal of the stories her story more ironic or tragic. (Whether other listed works would have fared so well is more difficult to tell.)

As a final note on the statistics, it would be interesting if the Hugo Award record-keepers would report the number of works that received ANY votes in a given year; in other words, to show that, out of the entire universe of eligible short stories or whatever, X received at least one nomination. The total number of nominating ballots is given in the statistics, but knowing how many unique works were on those ballots might give a glimpse into how homogeneous the reading tastes of the nominating cohort were.

****Wheaton’s Law: “Don’t be a dick.”

by

by