Not that it will make a difference; it’s just my opinion.

If the image doesn’t show up, it’s supposed to say “I Believe That Your Life Matters … And So Does Mine.” (Click for larger version.)

You may not agree. But I wouldn’t mind if you did.

Not that it will make a difference; it’s just my opinion.

You may not agree. But I wouldn’t mind if you did.

For us in the United States, today is Independence Day. Back in 1776, our Founding Fathers pledged their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to the pursuit of establishing the U.S. as a free country. Very shortly thereafter, the colonies-turned-states fought the Revolutionary War to secure their — and, by extension, our — independence.

Keeping in mind the price the patriots paid for the freedom we enjoy, it seems appropriate this week to consider this quote from Benjamin Franklin:

The way to secure peace is to be prepared for war. They that are on their guard, and appear ready to receive their adversaries, are in much less danger of being attacked, than the supine, secure, and negligent.

This seems to be an expansion of Vegitius’s observation, Qui desiderat pacem, praeparet bellum — “Let him who desires peace, prepare for war.” I feel certain that the well-read Franklin knew the Vegitius quote, but his addendum caught my eye.

Are we as a country on our guard, and do our enemies (or would-be enemies) see us as ready to receive their advances and blunt their attacks? Perhaps on the level of nation-states, yes: our armed forces remain strong and vigilant. But seemingly not on the lower levels, the levels of the day-to-day where individuals and small groups of radicals operate and where soft targets beckon. In general, as a population it would seem we are not prepared for war. We as a society have given that over to professionals — I was privileged and proud to be one of those professionals, once upon a time — but throughout history professionals have had difficulty adapting to new forms of war.

We seem loath to name this ongoing ideological conflict as “war,” however. (Over a decade ago I pointed out our reluctance to name war and attacks and enemies as such when it comes to the “recurring jihad.”) We seem unwilling, in the sense of being unable to muster the national will, to develop and pursue a coherent strategy to fight this war. Perhaps that is because we do not understand it. Maybe we have confused preparing for war with desiring war. But we have other instruments of power at our disposal besides the military instrument, and they do not seem to be availing us much.

Have we gotten to the point where we are “supine, secure, and negligent”? Perhaps not completely, but I get the impression that many people today who live in peace and relative safety take it for granted, as if it is our birthright and a permanent feature of our society. We would do well to remember that peace, like life, is precious and fleeting; it needs to be nurtured and protected, lest it be lost.

This week, after the fireworks have faded, I hope during our normal routines we will give some additional thought to our independence, our freedom, and give thanks for those who protect it every day — not just on the holiday — by being prepared to fight for it.

(Another entry in our continuing series of quotes to start the week.)

I thought of this week’s quote when I read business coach Chris Brogan’s newsletter, which I highly recommend if you’re trying to improve your connections with your customers.* On Sunday his newsletter focused on decision making, and it reminded me of a great quote I read years ago in Go Rin No Sho (A Book of Five Rings) by Miyamoto Musashi:

You must train day and night to make quick decisions.

I used that quote frequently when I was in the service, especially when I counseled the folks who worked for me on my expectations and their performance. As you might expect, decision-making was a key topic — the Air Force evaluation form had a specific section for us to cover “Judgment and Decisions.” And often the decisions we had to make were time-critical; for example, my own decisions about how to control and clean up rocket propellant spills and fires, or about diagnosing and repairing satellite ground systems to restore strategic communications.

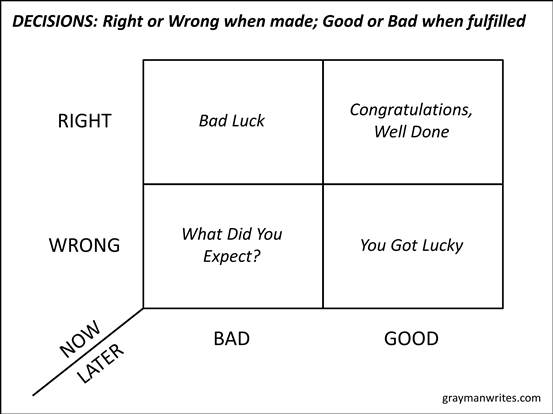

I told my officer and enlisted Airmen that when they started to feel paralyzed by a decision in front of them they should concentrate on making the right decision more than on making a good one. I explained that a decision is neither good nor bad at the time you make it, because the outcomes are still unknown: at the time we make a decision, it can only be either right or wrong.

That is, every decision is based on the situation as we know it, and in the case of crisis situations in which quick decisions must be made we almost never have complete information. But every decision is also inherently a prediction of what is likely to happen, and our predictions (sad to say) are subject to error.

A decision may be correct — the appropriate response to all the factors we’ve got in mind — yet still yield a negative outcome. Only after we’ve made the decision and have experienced the consequences can we make a value judgment of whether the decision was good or bad.

The right decision may turn out bad for any number of reasons — we may have missed some key factor, external influences may have come into play that were beyond our reckoning, etc. — but the possibility of a bad outcome should not paralyze us if we know what the right decision is in that moment. The fact that right decisions may have bad outcomes (and vice-versa, though it’s less likely) is part of the basic irrationality of the world; i.e., why the world, in some respects, fails to make sense.

Here I’ve tried to illustrate that when we make a decision — NOW — it’s either right or wrong, but whether the decision turns out to be good or bad is determined LATER. In my experience, it is unlikely for the wrong decision — one that is incorrect or inappropriate for some reason — to yield a good outcome, but it is at least possible.

If social media is any indication, many second-guessers don’t seem to recognize this temporal element to decision-making. Hindsight — that wonderful tendency to look in the rearview mirror of life and see how things might be different (strong emphasis on “might”) if only a different decision had been made — is only 20/20 because often our glasses are tinted. Whether rose-colored or some other shade, through those glasses we never see things as they really were, but only as we imagine they were, colored by all we know now. (Robert Frost was right about the saddest words in the world: “it might have been.”)

As an aside, this also makes me ponder the limits of machine decision-making. Will computer science get to the point that machines can formulate criteria on which to base a decision (knowns and possible unknowns, risks and rewards, potential outcomes, etc.); prioritize and weigh those criteria; evaluate the given situation according to the criteria; and then make a decision, observe the outcomes, and make a value judgment on the effectiveness of the decision? How many “do-loops” and “if-then” interactions do we go through with every single decision we make — even the trivial decisions, let alone the really important and sometimes time-critical ones? In our efforts to make a machine consciousness, will we be able to program those complex, dynamic processes into a machine? And since much of our decision-making operates outside of rational, conscious thought, will a machine’s unconscious (or, even, subconscious) processes ever develop to the point that it will not freeze when faced with a new situation requiring even a simple decision? This is partly why I’ve told panel audiences for years that I think the search for artificial “intelligence” is a bit mistaken. I maintain that artificial “knowledge” is necessary, in the full sense of theory of knowledge, for any machine intelligence to approach our own — and that is a much higher bar to clear.

But for now, when you are faced with decisions this week, I hope you’ll trust yourself to make the right ones, and that in so doing you will help train yourself to make quick decisions when they’re really necessary. The question of whether those decisions are good or bad will have to wait until you know all the consequences — but in my estimation making the right decision should make a good decision more likely.

___

*If you’ve spent much time on the Internet the last few years, you’ve probably heard of Chris Brogan — he’s only written a half-dozen or more bestselling books and built an extensive social media empire. If you want more information about him, check out his Owner Media Group, where you can sign up for his newsletter. (Or for something completely different you can sign up for my newsletter at this link.)

Some observations about conflict that may or may not be correct, and may or may not be about anything in particular.

As an observer of and sometimes participant in various on- and off-line conflicts — as I get older, I try to observe and participate less — I’ve noticed some behavior in myself that I suspect others may also practice to some degree. (To that end, I will cast most of this post using the royal “we,” but you are welcome to insert my name specifically if reading “we” bothers you.)

What I’ve noticed, in my own thinking and in the posts and comments I’ve read from allies and opponents alike, is that when we are faced with opposing viewpoints: we doubt, we devalue, we disparage, and we diagnose.

We Doubt. It seems we balance between gullibility and skepticism, and the degree to which we practice each depends on whether we trust the sources of particular information. To some extent we build our own “echo chambers” by tuning in more often to sources that appear to support our views of things; few people hold the same opinion of the Huffington Post as they do of Breitbart, for example, or of CNN as they do of Fox News. I suspect few go out of their way to obtain and consider reports from sources they do not favor, but at this level it is still possible to do so.

When we are faced with reporting on even simple matters from sources we have come to distrust, we simply doubt what we hear. This carries over from the presentation of facts to the presentation of opinions — especially when opinions masquerade as facts and when our own opinions become more important than facts. We can, however, reach the point where we begin to doubt even verified facts, demanding increasingly high levels of validation and distrusting even first-hand accounts if they contradict our own opinions or positions.

Simple doubt is the mildest reaction. But when doubt is not dispelled, when it lingers, it grows wild and even malignant. Doubt, unchallenged by facts or new theories, multiplies and metastasizes in the mind until we find it nearly (if not completely) impossible to believe. And then

We Devalue. When we let doubt become too strong, we may begin to transfer our disbelief onto the sources — even when the sources are people known to us. Little by little, perhaps, we lose respect for them. Sources we might once have considered credible we come to dismiss by reflex. And when we devalue a particular source enough, when it becomes worthless in our eyes, it becomes easy to disdain it.

We Disparage. This is broader than simply considering the source to be in error on a specific matter: this is rejecting the source entirely, on any subject. We begin to hold such sources in contempt.

At this level, when the source is a corporate entity, be it the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal, we cease to find any value in it and turn instead to other sources we do find valuable, and in so doing retreat further into the echo chamber in which messages reverberate and opinions ossify. When the source is a friend, a real human being with whom we may have broken bread, laughed, and even cried, the bad blood accumulates and we find avoiding contact more comfortable than resolving or even discussing issues.

How insidious this becomes when those sources are people. Friends we valued, whose opinions we trusted, we begin to treat in less friendly ways. Colleagues we esteemed, whose work we appreciated, we begin to disrespect. In the process we become more cocooned in our own preferences, inured to even the mildest overtures lest they damage our conceptions.

We Diagnose. At this stage we convince ourselves that our opponent — whether a once-close friend or a complete stranger — suffers from an illness or other defect, and we begin to formulate remedies. We rarely consider if we ourselves might be suffering from a similar malady, some incoherence of thought or some paralyzed grip on comfortable but unreliable theories. We consider ourselves healthy; perhaps not paragons of mental fitness, but certainly not afflicted in the way our opponents are. If only they would consult us, and imbibe the elixirs we are all-too-ready to prescribe, they would be well. Wouldn’t they?

___

Such It Has Ever Been, But Must It Always Be So? At the risk of stating the obvious, although sometimes it is necessary to state the obvious, only when we recognize something as a problem are we ever motivated to change it or solve it. And we may differ on whether a particular thing is a problem.

In the colonial era, for instance, loyalists did not recognize the same problems that the Patriots recognized. They saw the same things happening, and perhaps to some degree were also uncomfortable with them, but they did not recognize them as problems that needed to be solved. As a result, they almost certainly disapproved of the methods that the Patriots used to address the problems that they saw. The loyalists and the crown considered the people we call Patriots to be rebels, and such they certainly were. And in the end, the differences became too severe to be reconciled and the stakes were high enough that open battle ensued.

In contrast, often we find ourselves embroiled in low-level, non-life-threatening conflicts — perhaps matters of some consequence, but certainly not matters that demand unbridled vitriol and venomous attacks. In such cases, we may hope that we could detect when we doubt without affording any benefit of the same; when we shade from doubt into devaluing; when we begin to disparage someone else; or when we diagnose another’s supposed condition. And, having recognized the pattern, we may hope to moderate our own thinking before we irreparably damage our relationships or reputations.

We may further hope that our opponents could recognize the tendency in themselves and refrain as well, but we have responsibility only for our own thoughts and actions. May we use them well.

One of my newsletter readers suggested today’s quote to start the week,* an entry that is often attributed — wrongly, it would seem — to Theodor Geisel, a/k/a Dr. Seuss:

Those who mind don’t matter, and those who matter don’t mind.

I like the sentiment, especially where unfair or unkind criticism is concerned, but I was unable to find out where this quote originated. Several sources credited U.S. financier Bernard Baruch with a version of the quote — which interested me, because my hometown is very near Baruch’s retreat at Hobcaw Barony on the South Carolina coast — but its earliest use in print appears to have been in a British engineering journal in 1938, and it seems to have been in use well before that.**

Nevertheless, the quote is a good reminder that the opinions of others are not created equal (so to speak). We are bound to encounter criticism, some of which will be valuable and some we can disregard, but this quote speaks to something beyond criticism of work we’ve done or art we’ve created.

At a deeper level, it speaks to the criticism we may receive not because of what we do but because of who we are: choices we make, things we believe, emotions we display. In those cases especially, when the critic seeks to injure rather than edify, to heap scorn on us rather than inform us or others, to point out imperfections they perceive rather than help us chip away at them, it is good to remember that those who mind what we do or who we are don’t really matter — and those who matter will accept us and our work and build us up rather than belittle us.

(I’m reminded of Teddy Roosevelt’s “man in the arena” quote — the one that begins, “It is not the critic who counts” — but we’ll save that for another day.)

Meanwhile, “Those who mind don’t matter, and those who matter don’t mind” is a good quote to carry with us this week, to guard against any unwarranted criticism we will face. And I’m trying out a corollary: Don’t pay it any mind, unless you think the critic matters.

___

*If you like, sign up for my newsletter — it’s free! and it only shows up once or twice a month.

**The “Quote Investigator” site offers a run-down on its history, so far as they could discern it.

Happy (?) Tax Awareness Day! Yes, it’s the Ides of June, and time once again to think about taxes.

If you pay your taxes quarterly, then today’s the day.

If your employer withholds taxes from your paycheck, however, or you have an accountant who takes care of such mundane things for you, it’s a good day to remind yourself how much in taxes you’ve paid so far this year. I encourage you to take a look at the last pay statement you received in May and note the “year to date” figures of how much you made and how much was taken out for Federal, state, and other taxes.

What do you think of what you paid? You may think it was too much, or too little, or just enough; I don’t know. You may think of the things you could’ve done with that money, if you could’ve kept some of it. You may think of it as contribution; you may think of it as confiscation. Perhaps you may think about all the things the government does with your money.

For this Tax Awareness Day, here’s another oddball tax-related idea I had. (“Another” because I’ve tossed out a plethora of tax ideas over the years.) Instead of having flat amounts for the maximum contributions a person can make to retirement plans, have the total amount increase incrementally with age.

Each type of retirement plan has its own rules and limitations, all of which serve to make the tax system even more convoluted than it would be otherwise. For instance, the maximum that can go into a 401(k) through an employer is currently $53,000 (not counting any “catch-up” contributions), unless you make less than that in which case you can only put in as much as you make from that employer. In contrast, individual retirement account (actually, in IRS parlance, “arrangement” rather than “account”) maximums are currently $5500 for everyone up to age 50, then $6500 after that — again, not counting any “catch-up” amounts.

What if, instead, the total amount for all retirement plans was a multiple of age? If the maximum was set at, say, $2500 times age, then an 18-year-old could invest $45,000, a 22-year-old would be able to invest $55,000 — more than the current employer-plan maximum — and so forth. (I prefer “invest” to “contribute,” because we hope that retirement plans will grow with time; the end result may be the same, but investing in the future seems a bit more compelling than contributing to it.)

Why have the amount increase incrementally, and would it make any difference?

Ideally we have more money to invest as we get older, either by virtue of getting better jobs or by having lower expenses over time. And some of us — perhaps many of us — didn’t learn the lesson that we should invest as much as we can as soon as we can; thus the “catch-up” allowances that are already in place. Most of us may never be able to invest the maximum amount, of course, and those of us who aren’t very good money managers may never invest very much, so raising the limits may make no difference in most cases. I guess it’s possible that this kind of incremental approach would make the system more complicated, rather than less, but to me it seems it would at least be easier to understand.

Regardless, I hope you enjoy the rest of the summertime Tax Awareness Day.

Do you know any modern day Pharisees? You might. Consider this quote to start the week, from A.W. Tozer:

A Pharisee is hard on others and easy on himself, but a spiritual man is easy on others and hard on himself.

If you’re unaware of the reference, the Pharisees were a branch of Judaism — a political faction, if you will — that emphasized purity and strict adherence to the Torah (the Law). If you’re uncomfortable with the language of religion, we could conceivably use “hypocrite” in place of “Pharisee” in the quote, but for me “Pharisee” carries a stronger meaning. A hypocrite claims to have a high standard but does not live up to it, but need not insist that everyone else hold to that high standard; many of us are hypocrites about something or other. But when the message is “do as I say, not as I do” — when we give ourselves a pass but insist on better behavior from others — then we have shaded into the realm of the Pharisee.

I also think the idea in the quote extends beyond the realm of religion. For instance, we could replace the word “spiritual” in the quote with “enlightened” and arrive at much the same place.

When we insist on a standard for others that we would be hard pressed to meet, rather than holding ourselves to a standard even when no one else is watching, then we are being Pharisaical. And we can be Pharisees in many different ways. In matters of health, for instance, when we insist that we know best how other people should eat or behave or interact with their physicians but we allow ourselves small indulgences — or maybe large indulgences. In matters of civics, when we insist that we know best how other people should educate themselves or vote or act — or when we insist that they must change their opinions about how we think or act.

It is Pharisaical to insist on tolerance but to act intolerantly — to say without saying, “You must accept me and what I do, but I will not accept you or what you do.” It is Pharisaical to remain willfully blind to demonstrable facts and clear logic and to silence or censure those who present facts that cast our reality in different light — to say, “You must change the way you think; I will not.” It is Pharisaical to view with crystal clarity the errors, lies, crimes, sins, and endless peccadillos of others, but to overlook or blur the distinctions of our own.

That’s why I think the “Mirror” image is a good choice for this idea. The Pharisee in us — and I include myself among those who can be Pharisaical — may see ourselves differently than others see us. Perhaps it’s even worse than a lack of focus when we look at ourselves: perhaps we have painted on the mirror a false image, and have looked at it so long that we believe it’s real. But those who observe us know better.

So, do you think you know any modern day Pharisees? You can probably identify one or two. And you might even be one, in some way about some thing. I have that tendency myself, and I struggle against it every day.

Thank you, as always, for spending a few moments with me here. I wish you the best in your struggles, whatever they may be.

I spent the weekend at the ConCarolinas science fiction and fantasy convention, where I had the great pleasure of talking with a few people about my novel that’s in the publication pipeline — which is a bit surreal to me — so it seemed fitting to select a quote that relates to books to start the week. Teddy Roosevelt wrote,

Books are almost as individual as friends. There is no earthly use in laying down general laws about them. Some meet the needs of one person, and some of another; and each person should beware of the booklover’s besetting sin, of what Mr. Edgar Allan Poe calls “the mad pride of intellectuality,” taking the shape of arrogant pity for the man who does not like the same kind of books.

All of us who write and who hope our writing reaches an audience would do well to remember that some of what we publish will “meet the needs of one person, and some of another.” That follows along with Lincoln’s observation about not being able to please everyone all the time. We can only hope that our work finds its way to those who will appreciate it, and perhaps even to those who will value it.

But Roosevelt is right that we should beware of dismissing books that meet other people’s needs, and thereby of dismissing those other people. In the science fiction and fantasy field, especially recently, fans and even authors have taken sometimes excessive delight in disparaging works we consider hackneyed or offensive or otherwise worthy of derision.

In some cases we’ve reacted to what we perceive as unmerited success (“How could so many people buy X?”), and in our most self-conscious moments we might admit to coveting that success for our own work. Alternately, we might think we are being discerning, perhaps even sophisticated; we might think we are making important statements about art and its relation to the world; we might just be trying to make a joke.

Regardless of the reason we find to scorn a book or someone else’s taste in books — we dislike the author (or the person) on some level, we prefer another subgenre, we haven’t had enough fiber that day — we would do well (I would do well) to realize that what we think of as a book’s faults or merits will differ from what someone else thinks, and we should allow one another our different opinions. The market, and time, will always be the final arbiters.

So, do you like books? If yes, great! If no — if you don’t like any books — then maybe you just haven’t found the right books for you yet. I hope you’ll keep looking!

And if so, what books do you like? Excellent! Whatever books you like, for whatever reason, that’s wonderful. Keep reading!

And have a terrific week!

Today we celebrate Memorial Day. I hope you find today’s quote, from the Gospel of John, the fifteenth chapter, the thirteenth verse, fitting to start the week:

“Greater love has no one than this, that one lays down his life for his friends.”

On Memorial Day, of course, we remember those who laid down their lives in defense of the United States. They laid down their lives for their friends and family, yes; for their comrades in arms, certainly; but also for us. The freedom we enjoy was bought at a tremendous, terrible price, and we do well not to squander it.

It seems a good day also to remember the last verse of “The Star-Spangled Banner,”

O thus be it ever when free men shall stand

Between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n-rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto — “In God is our trust,”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

To which I say, Amen.

So, enjoy this day — and I mean really enjoy it, find joy in it, take joy from it, share your joy with someone else — but spare a moment to reflect on the freedom we enjoy, and the price that was paid for it. It is precious, beyond measure, and we should use it well.

I hope you have a fantastic week.

On this date in 1788, my home state of South Carolina became the eighth state to ratify the new Constitution of the United States of America. Given the (perhaps unusually) contentious nature of our political discourse this election year, it seemed like a good idea to use the Preamble as today’s quote to start the week:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Break it down with me …

Our Constitution was not perfect when it was written, but it was not expected to be; it was only meant to be “more perfect.” Its authors were wise enough to include in it the means to change it should future years prove it unequal to its charge. And what was its charge, its mission? It seems to me it’s right there in the Preamble: not to institute a governmental system for its own sake, but to accomplish certain tasks that together would free its people — “We the People of the United States” — to pursue their own aims, their own dreams, their own potential.

As we begin this week, I hope you have success in pursuing your aims, your dreams, and your potential.