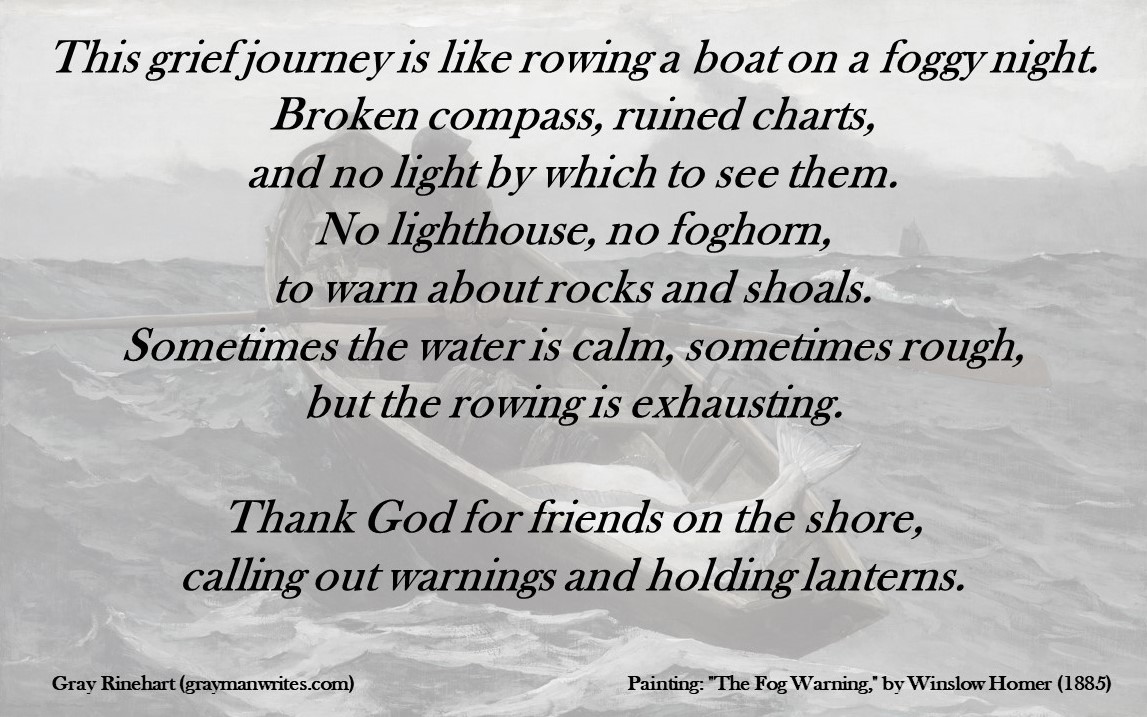

Fair warning: This will be a long post — as in, short story length. It’s the last in the tribute series to my late wife, Jill Rinehart, who died in the early morning on this date in 2019. All the entries (linked at the bottom, if you’re interested) form a record of my grief and my struggle through it, and though I know the struggle will continue, it’s time for this series of posts to end.

I wrote this in sections over a fairly long period of time. As a result, it may come across as a little disjointed….

My Jillian

I started calling Jill “Jillian” when we were in high school, and I was the only one to do so. She signed her name “Jill” to everyone but me, and once or twice when other people called her “Jillian” she either corrected them herself or asked me to do it. It was my special name for her, and no one else’s.

Yesterday: A Day of Remembrance

Yesterday, I relived parts of Jill’s last day, in an attempt to remember and honor her. That day in 2019 was difficult but not entirely bad … but then it gave onto the worst day ever.

Yesterday was a fine, beautiful, blue-sky day — much as it was last year. I walked the pup around the soccer fields, as I’d done that morning when Jill went to her doctor’s appointment (which I should have gone to with her, but she didn’t think she needed me to). In the afternoon, I took Twix with me to the NC Art Museum, since that’s where Jill had gone to relax after her appointment freaked her out, and we spent a little over an hour walking the grounds and chatting with Stephanie.

In the late afternoon, I went to the restaurant where the two of us had supper; I ate alone, with Jill’s picture on the table across from me. And as the sun was setting Twix and I walked the last walk the three of us had taken together at Bond Park. I recalled, as much as I could, what we talked about and how we joked and cut up and generally had fun, neither of us knowing that would be the last time we would ever walk together. Christopher met us at the end of the walk, and we talked a while about his mom and how much she meant to us.

Later in the evening, I went up to Jillian’s art studio, because that’s where she had gone that night a year ago. She had spent the remainder of that evening making example pieces for a Halloween-themed tic-tac-toe set (with its own little tin) that her class was going to make the next day. She had shown the pieces to me, including the little clay Jack-o-Lantern, before she baked them to set the clay, and put everything in the tin before she came to bed that night. It had sat on her studio desk ever since, but last night I finally opened the tin and played a game of tic-tac-toe with the set she had made.

When bedtime came, I laid on her side of the bed for the first time ever, just to feel a little bit closer to her. I prayed to sleep through midnight, which thankfully I did, and not to dream of her last gasp; and, truth to tell, I prayed a little bit that I might not wake up at all, just as I had done in the early days of her being gone. But wake up I did, to finish this tribute.

I wish I could have dreamed of her, looking back at me as she walked up the steps to the next world. I hope when my time does come that she will extend her hand back to welcome me.

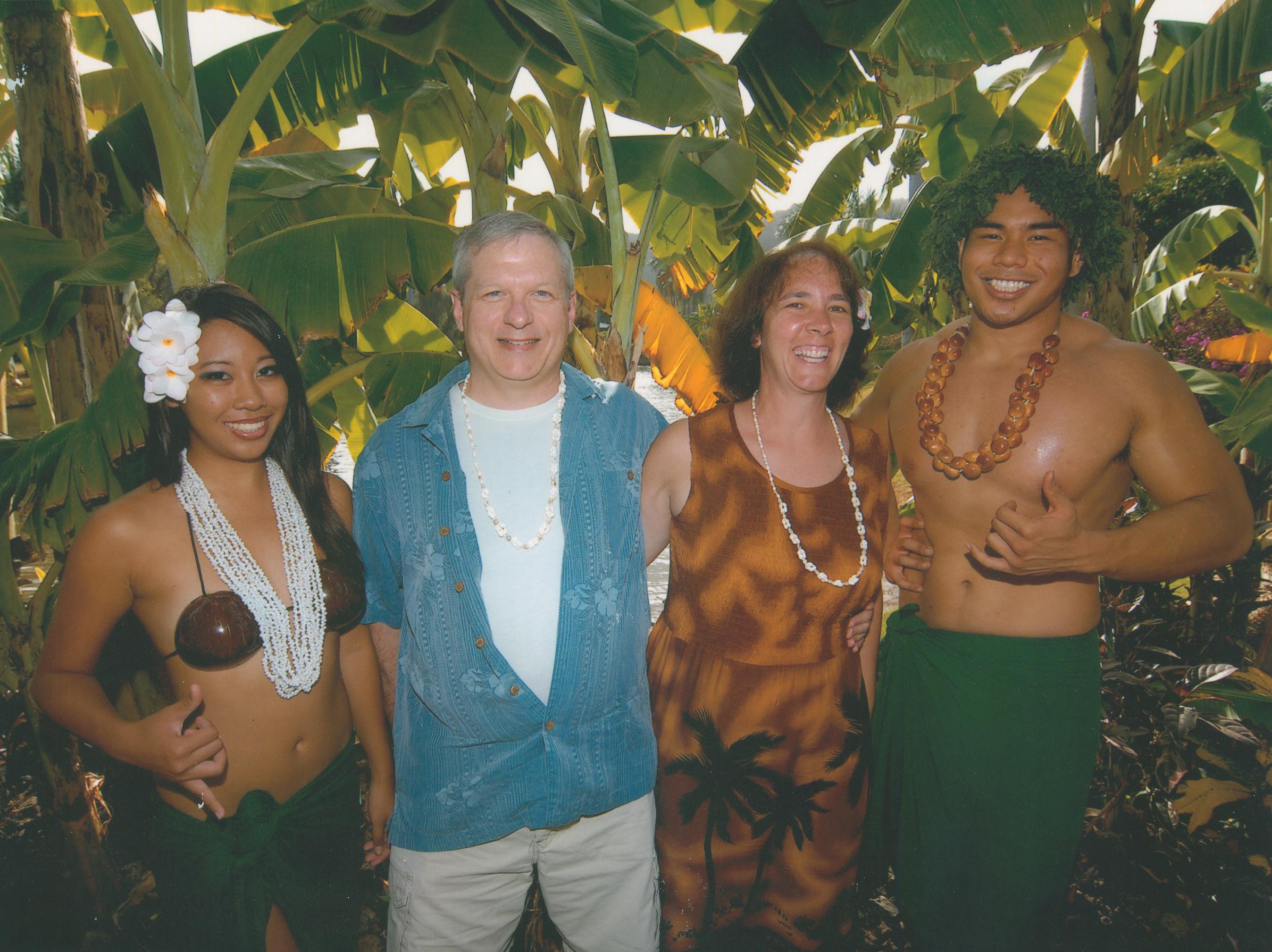

(One of my favorite pictures of Jill, taken at Brookgreen Gardens in 1982 by her brother Jeff Briggs. She’s wearing her prom dress, and I love the playful way she’s looking back at the camera. I imagine her walking up those steps into Heaven, and looking back to say that everything’s okay.)

Where I Am Now

I am lost and I am found. Weak and weary. I tried to reach outward, failed, and have been collapsing inward.

On the advice of counsel — i.e., my therapist — for most of the past year I’ve tried to catalog pleasant memories of my time with Jill. Where I’ve succeeded, it’s because we had many good times together. Where I failed, it’s either because I’ve let some bad time overshadow the good or because (as I’ve mentioned in previous installments) my memory is not as reliable as my imagination.

I know it’s unrealistic to wish that I could recall every movie we saw together, every dinner we had, every time we hiked in the woods or walked on the beach or did anything where we talked and laughed and enjoyed one another’s company. I’m grateful that there were enough of those times that they begin to blend together and don’t stand out from one another.

Of course I’ve enjoyed looking at photographs she took when we were together, and even though my memory of the specifics may be faulty I can recall enough to know that we enjoyed those trips, those evenings in the park, those dessert treats, those simple pleasures. But I also know there were times I missed, and I hate having missed them. For instance, I look at the hundreds and hundreds of pictures she took when she went on outings by herself, on what the author of The Artist’s Way called “artist dates,” and while I know she enjoyed and was energized by those outings I find myself wishing that I could have gone on many (if not most) of them with her. And if I dwell on that kind of thing too long, regret piles on regret.

I just still miss her very much. I find it difficult to express how much I miss her — more on that later — and how badly I still wish she would be waiting for me when I get home, or how badly I wish I would look up to see her pulling up in the driveway, or how badly I would like to wake up in the morning and know she was there and have to sneak downstairs to let the dog out to avoid waking her up too early.

Memorable Moments

Where my memories have been weak, over the past few days I’ve tried to recharge them by re-watching some videos from when our children were young. Jill had done so last year in advance of working to make them into digital movies; she only ever completed one test movie, but it’s nice to think that a lot of her down time last year included revisiting those memories.

I’ve been a little bothered by watching segments in which Jill filmed the children while I wasn’t there. Some made sense — for instance, they spent the day at the beach at Vandenberg AFB while I was at work — but some hurt, like the Easter egg hunt I missed because the Air Force had sent me elsewhere for that weekend. I hate that I missed those moments, though I realize that it would have been impossible to be available for all of them. But I also miss the moments we did have together, and even more the moments we could have had.

Before I started the video watching (which I haven’t finished yet), I also read through the journals I kept for a few years. They weren’t diary entries — most of the notes were snippets of articles or stories I was trying to write — so I didn’t record very many details of the days, and when I did it was usually because something had gone wrong. Reading them was not altogether pleasant, then, but I did discover some entries that made me smile:

- 3 December 1993: A note about walking down the street and having a streetlight go out reminded me of a specific memory of walking with Jill down the sidewalk at Clemson when we were students. We had been approaching Riggs Hall (with Tillman Hall at our backs), and I decided in a fit of exuberance to swing around one of the light poles in somewhat the same way Gene Kelly did in Singing in the Rain. But as soon as I did it, the light went out! That took us both by surprise, and we laughed together and ran down the sidewalk for fear of being caught. And from then on, from time to time we would walk past a light pole and the light would go out, and we would laugh together at the memory.

- 22 July 1994: I wrote that Jill, who loved to build our fires when we went camping, “threw some old potato chips into our campfire and we watched them flame up from the oil they were fried in,” after which we discussed which brand of chips would work best if we needed to build a fire quickly.

- 2 March 1995: “I am so happy, so pleased with the love and care Jill puts into our lives. For Stephanie’s birthday cake she used Lion King decorations; for Christopher’s she used miniature trucks and tractors. She is a wonderful wife, a great mom. I can’t do enough to show her how much she means to me.”

- 13 March 1995: “I may not write many of the stories I’ve got rattling around in my skull, but I think afternoons like this one — playing Frisbee with Stephanie and Christopher and Jill — may make up for it.”

- 20 March 1995, when I was traveling on temporary duty: “I do so enjoy the little notes Jill leaves for me in my luggage; if she traveled more I could return the favor more often.”

- 3 August 1995: “Read an old letter Jill wrote to me — she found it today in her cleaning up for our move. I am still surprised that she fell in love with me.

“I’m glad, but I’m still surprised.” - 19 August 1995, while I was in training for that next assignment: “Jill, Stephanie, and Christopher are safe in Colorado Springs — thank God for Alexander Graham Bell’s magic machine. If only I could send my arms with those electrons and give them a hug.

“I can hardly keep my thoughts straight: I think of how loving Stephanie is, how much fun Christopher is, how beautiful and caring Jill is. I miss them so. I want to come home and have Steph and Chris run to hug me — I want them to seek me out wherever I might be to show me their latest creations or tell me about something that happened that day. I want to stop Jill on her way to do something and give her a hug — she complains when I do it that it’s just to annoy her, but I think she needs those hugs as much as I do. I like hugs.” - 22 March 1996: “Just back from comet gazing. Hyakutake looks pretty good, even through a pair of binoculars. I’m not sure if Stephanie and Christopher could really pick it out, or if they just said they could so they could get in the van. Jill enjoyed it though — I am very fortunate to have a wife who enjoys the same things I do — when we got back from our jaunt (we had driven eastward to get away from most of the city lights), she lay on the front lawn to look at it some more. (It was visible here at the house after all, but not as bright.)”

- 9 June 1996: “I often wonder how I got where I am. How was I able to convince my Jillian to marry me, and how have we been able to build a (relatively) stable family? How have I been able to enjoy this level of success in (and out of) the Air Force? The short answer is, I don’t know.

“I certainly feel blessed.” - 25 June 1996, after a couple of difficult days: “Our night on the beach was close to being perfect. The moon had set, and the only lights came from stars and beach houses — most of the houses were dark, and the brightest lights were diffused glows of condominiums to the north and south. Where we were and where we walked, we enjoyed the darkness; reflected glow from the shallow water framed our footsteps.”

- 4 July 1996: “The four of us sat on the blanket, playing rock-paper-scissors while we waited for the fireworks to start. Fireworks and Frisbee, root beer and rice crispy treats, a blanket in the grass — in such moments, few and far between as they are, I can forget the rest of the world and allow myself to be happy.”

- 15 June 1997: “So insignificant they may seem to an observer, they are priceless to me: the little touches, the holding hands, small expressions of intimacy, but vital and important to me.”

- 16 January 2001: “I realized the other day that sometimes I’m afraid to admit how much I love her. Even to myself. The magnitude overwhelms me, and I’m afraid to think about it for too long.”

Some entries were not so sweet, though, and made her loss and my grief even more palpable:

- 19 September 1995: “Why do I torture myself?

“Why do I play these scenarios in my mind?

“I should not ask why, the answer is too clear: fear. I am afraid of that which has always unnerved me, that thing that happened once, long ago, in another time, another place. I am afraid of losing her, of not getting her back. Maybe it is a function of missing her, wishing I could touch her, hug her, rub her feet, brush her hair. I force myself to take deep breaths to slow my heartbeat — my evil imagination is working overtime.

“It doesn’t matter which scenario plays — they all leave me breathless, gasping, sweating, shaking. I swallow down the nausea; I wish my intestines would unravel. Sometimes it is death. In the course of hoping she is safe I encounter the fear that she is not, until that fear takes control and I hear the telephone ring, the voice on the other end with horrible news. The tears I fight are real enough. Sometimes it is my death — a near miss in an automobile or a news report or whatever, and suddenly I see her receiving the word and I want to hold her, tell her it’s not true, dry her tears and kiss her eyes and make it all right again. But I cannot, and again I fight my own tears. Sometimes they win.

“In these imaginings I lose her forever — I feel as empty as a balloon….” - 19 November 1995: “What is it about a woman’s tears?

“What is it in me that wants to conquer them, overthrow them? That wants to hold Jillian so tightly my arm starts to ache, that wants to wipe away or kiss away those tears — but that is not enough.

“The tears are not the problem — the stress and pain pushing out the tears is the real problem. And unfortunately I am more part of the problem than the solution. I am caught in a bizarre and unintended hypocrisy: treating and causing the symptoms at the same time.

“Would that I were wiser.” - 9 February 1996: “A photograph cannot hug you back. Pictures never call your name. They are mute, lifeless reminders, silently echoing empty promises.”

- 19 June 1997: “Jill says she is getting tired of my insecurities. She has no idea the depth to which they run.”

- 25 July 1997: “Lord, hear my prayers, see my tears.

“Do dreams really come true? I want to believe they do, they have — her love for me, my love for her, our love for each other seem too much like a dream that came true, too good to be true. Why can’t I accept it?

“I want to trust you. I want to abandon myself, but I hold on to myself too hard. I want you to make me whole again.

“Lord, please send this message to Jillian while she is away: please let her know how much, how fervently, how completely I love her. Please let her know I am still in love with her. Please let her know how much I miss her, how much I need her, how much of a blessing she is to me, how sorry I am for always hurting her, how badly I want to make things right again.

“Thank you for listening. Lord, please fill me with your love, with your spirit, with your peace.” - 27 February 1998: “A thought occurred to me while driving into work this morning: how sad it would be to die at work. Sad to die anywhere, that is (I seem to be over my latest thoughts to the contrary), but especially sad to die, say, at one’s desk amid the day-to-day mix of tedium and stress that is the work world.

“Better, it seems, to die at home amid the day-to-day mix of domestic tranquility and strife. Why? It seems better to die among those you truly love, to be able to have your last thoughts of them and maybe even tell them how much they mean to you, than to die miles away from them among people who are mostly only acquaintances rather than friends.

“Maybe.” - 2 July 1999, when the family was on vacation while I was working, an entry that rings truer than ever in my grief: “This morning, in the all too brief moment before I woke fully, I could almost believe Jill was there with me. It seemed, for that instant, that I could have stretched out my arm and put my hand on her — but then I was awake, the moment passed, and I was alone. Maybe more alone than before.”

- 29 August 2007: “Things keep happening so fast, it seems — days full of activity (which is good), but little time to reflect (not so good)….

“Daily now I pray that my family will have good days at school — Jill teaching (that is, helping the teacher) at Chesterbrook, Steph at UNC-G, Chris at Green Hope — and I wonder if I’ll get to go back to school myself someday. I think I would like that, but it’s not going to happen anytime soon. Not with the budget so tight that I may have to borrow money to pay the tax bill next month.

“Things certainly haven’t worked out the way I thought they would since I retired. Maybe they never do, and maybe that’s okay.”

No, things haven’t worked out the way I thought they would. And I can say with certainty that it’s not okay for me.

How Much I Miss My Jillian

In truth, I cannot express how much I miss her. I don’t want to overstate the case, but the simple fact is that I do still miss Jill, and I suspect I always will to some degree. I know I want to always remember all the best things about her. I hope that makes sense.

I thought maybe I was getting better — “better” is not really the right word — over the summer, or that I was getting more used to things, because the periods of sadness had started coming less often and in many respects had been stinging less. It had become a simple fact, that I just missed her, rather than something that controlled my reactions or dominated my days.

The last two weeks gave the lie to that. Partly, that’s been because (as mentioned above) I’ve immersed myself in scouring old journals and watching old videotapes for any mention of good times we had. I’ve been able to laugh at things we said, and smile at the way she took care of the children, and let her voice wash over me and feel the love I had for her. What a marvelous experience! The still pictures we downloaded from her computer or I scanned in from old photographs, the artworks on the walls, the clothes in her closet or books on her shelves, lack that immediacy, that impact.

Instead of trying to quantify how much I missed Jill, early in 2020 I started making a list of things I missed about her. I added to it over time, until now it is quite lengthy. In general, I miss the things we did together, and the things she did for me and the things I did for her. I deeply miss the security of having a partner in life, or at least the feeling of security that I had because I had a partner.

Some of the many things I miss about my Jillian, in alphabetical order because I couldn’t figure out any better way to sort them:

- Brushing her hair

- Buying her flowers as a surprise, whether I put them in a vase or hid them in the refrigerator for her to find them, and hearing her reaction (usually something like, “Oh, pretty!”)

- Going light-looking at Christmastime (from very early on, when we went to see the lights at the Hammock Shops in Pawleys Island), or going to any special holiday celebration — a play, a cantata, the “Lessons and Carols,” anything

- Going out to breakfast with her on Saturday mornings — we had a rotation of local places, some of which she gave her own names to — or going out to eat with her anywhere, whether for a casual meal or a formal affair like an Air Force Dining Out

- Helping her when I could, whether with her work or around the house or wherever (which I don’t feel I did often enough)

- Holding her hand

- Hugging her — including interrupting her when she was headed somewhere or in the middle of some chore (it irritated her some, as I noted in a journal entry, but I think she still appreciated it)

- Kissing her hello or goodbye or for no reason whatsoever, and often with a double kiss for emphasis

- Laughing with her, whether at a TV or improv show or at something one of us said — even when it was inappropriate, like during communion one Sunday morning at Springs Community Church in Colorado Springs: As we took the bread, we both sniffed at it a little bit and Jill leaned over and said it smelled like tuna, to which I replied, “Yeah, it’s the loaves and the fishes” … she sat there for a second or two, and then she started to chuckle, and then we both put our hands over our mouths to keep from laughing too loud … it was terribly irreverent, but it made for a memory we recalled several times in the years since

- Listening to books on CD on long drives, or reading to each other — and when Steph and Chris were old enough, having them read to us

- Listening to the ideas she had about her art classes, and her listening to any oddball suggestions I made

- Looking at her artwork — for instance, having her come to the railing outside her studio and hold up something she’d just finished for me to see

- Opening the car door for her, or opening doors for her when we went somewhere

- Opening the front door for her to welcome her home, from school or work or the store — and telling the dog, “Mama’s home!”

- Playing games — whether just games of Scrabble or Rummy between the two of us, or larger games with family and friends

- Rubbing her feet

- Saying “I love you,” and more than that, hearing her say it — something we did several times every day we were together

- Sitting in the same area together, whether on the couch watching TV, or on the front porch enjoying the sunshine, or anywhere we could talk or laugh together

- Smelling her cooking

- Smelling her perfume (she never used much)

- Talking about things we wanted to do or places we wanted to go

- Talking about what we had read or seen or done that day

- Telling her about my story ideas or letting her read my lyrics-in-progress, and hearing her feedback

- Walking with her — with or without dogs, in the neighborhood, in the woods, on the beach, in the mountains — which may be why that last walk we took together became so important to me

- Washing her back

- Watching her bathe

- Watching particular things with her on television — for instance,

- The Big Bang Theory, and laughing at ourselves because the show makes fun of nerds and we were both nerds

- The Amazing Race, and talking about the places we might visit and whether or not we would be able to complete the challenges … and whether or not we would still be together if we tried to do something like that, or if the pressure of it would tear us apart

- House Hunters International, usually before we went to sleep, and talking about the places we might want to go (and the places we would never want to go), and which house we thought the people should choose — the DVR in the bedroom is full of over 200 episodes I haven’t been able to watch

- and some additional shows that she liked more than I did, like Survivor or Dancing With the Stars — I didn’t watch them regularly with her, but I tried to catch them once in a while just to be close to her and talk about the things she liked

I suppose anyone who had a good, long-lasting marriage could make a similar list, and can relate to the sudden absence of things that might individually seem almost insignificant, but together were absolutely priceless.

That Regret for Which I Was Most Unprepared

In the first “Unprepared for Regret” installment, I included this in the list of regrets:

… things I’ve learned about that I didn’t know, that at times during our marriage she was unhappy or dissatisfied or depressed: specifically, for not having clearer vision and more wisdom to see what was wrong and know how to help; for being self-absorbed and ignorant … not uncaring or unconcerned, really, but stupidly blind to her needs

The more I’ve learned from letters she kept, the more I’ve come to realize that the regret for which I was most unprepared was her regret — that she at times regretted marrying me or being with me. Dwelling on that has come very close to destroying me over the past months. Every time I think about her being sad, or ever wishing she was somewhere else, I feel as if my heart is going to implode.

I have no way of knowing how many times over the thirty-four years of our marriage that Jill wished to leave, or how far she might have gone in planning to leave. I know that one time a friend wrote to warn her about the worst-case scenarios in divorce, and another time her parents wrote to her about going back to live with them when Jill felt I was smothering her. Why she didn’t leave, I’ll never know.

Fifteen years ago, for instance, Jill gave me a choice — an ultimatum — between her (and the family) and the Air Force.

That story starts with Jill calling me as I was getting ready to leave work. (I was working out near Dulles Airport that day, instead of in the Pentagon.) She said she was out in the area, and asked if I’d like to meet her for an early supper. When I got to the restaurant, she said she had an overnight bag in the car and reservations at a nearby hotel if I was interested — but that first we needed to talk.

And talk we did. She was tired of the strain the Pentagon assignment was putting on the family and our relationship, and told me very clearly that if something didn’t change I would come home one day and she and the children would be gone. My reply was simple: At the first opportunity, as soon as I was eligible to retire, I would put in my paperwork. Because she and the family were more important to me than my career.

But the point is that my Jillian thought about leaving me, thought her life would be better without me — or at least without that version of me.

Let me be clear that I have never thought of myself as perfect in any way. In the manner of all of us being our own worst critics, I probably magnify my faults in my own sight (I am very close to them, so they appear large, and I scrutinize them quite often), but I know my faults are legion. But facing my imperfections has been easy compared to facing what I now see as the abundantly clear imperfections in my marriage. I’m not sure if I thought our relationship was unassailable, or if I believed that her devotion matched mine, but to find that at any point she earnestly desired to leave — that she had any regrets about being with me — has been a heartbreak far beyond that of losing her.

I was utterly unprepared to learn that.

And, yet, despite whatever misgivings she had, she stayed with me. We worked out the things I knew about, and she somehow worked through things I didn’t. She remained my wife and my life partner, in the best sense, in the sense that she stuck around when she could have left.

And then suddenly, unexpectedly, a year ago she was gone, and I lost every chance to apologize or make amends for how I had hurt her.

All I Ever Wanted

It’s strange that I didn’t find the words to articulate this until yesterday.

You may think that I’m about to write that Jillian was “all I ever wanted” in a woman, or girlfriend, or wife, but that’s not exactly it. Who’s to say that someone else might have been just as good a partner, just as good a friend, just as good a mother? No, the thought I had yesterday had more to do with our relationship as a whole, than with her as a person.

So here’s the indivisible bit at the core of my relationship with Jill: All I ever wanted was for her to be proud to be my wife.

Not necessarily proud of me as a person — as an Air Force officer or writer or whatever, as a husband, as a man — though that might be part of it. Not necessarily proud of our children, though she had every reason to be (and was more responsible for their good qualities than I ever was). Not proud of what we had in terms of our house or material possessions, because while we did okay we remained contentedly middle class.

No, I wanted her to be proud to stand by my side. Proud to sign her name “Jill Rinehart.” Proud to introduce me as her husband, or for me to introduce her as my wife.

It was a crushing blow to learn, as I mentioned in the previous section, that she sometimes regretted being married to me. But I think at least sometimes — during our better days, and I hope particularly during our later days — she was able to be proud of our marriage.

I wish she were here, so I could ask her, but more so that I could do whatever it would take to make her proud.

I always said I would do anything for Jillian. And maybe what I’m doing now counts for that. Maybe trying to honor her by writing these words, or by posting our best memories on Facebook, count for that. Maybe my tears, maybe bearing the sadness and the pain and the grief, are part of what I pledged to do for her. But would they make a difference? I don’t know.

Better Life

I believe that my life was better because Jill was in it, and I hope that most of the time she thought hers was better with me. I think we made a good team, and I hope she would agree.

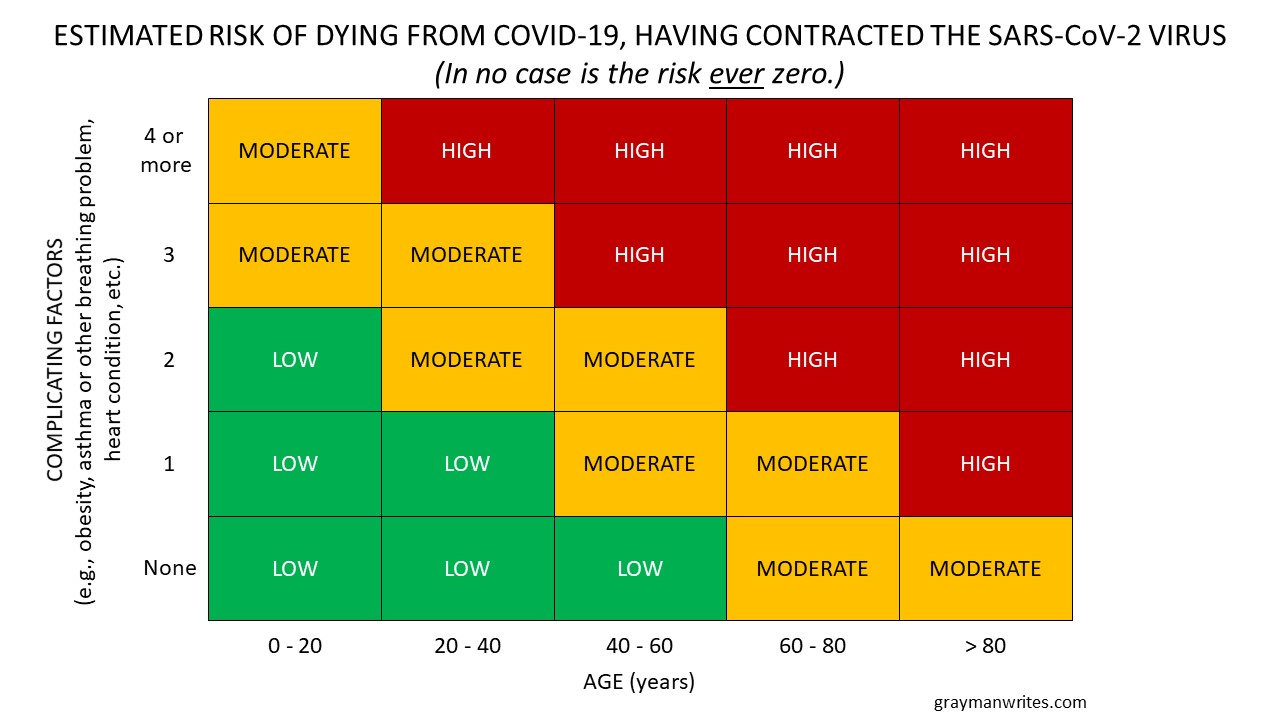

I believe my life would be better if she were still in it, but I don’t know if hers would be better if she were still here. She was very afraid something was going to happen during her surgery or her recovery — we talked about it the day before she died, but I only recently learned that she had also confided her fears in one of her best friends. Maybe the surgery would have gone well; I have no way of knowing. But even if it had, the recent virus hysteria would have been very difficult for her, and she might have been miserable for the past year — or even taken ill from it. It may well be that losing her a year ago meant that we didn’t have to see her suffer. That’s hard to accept, but I suppose it would be a fair trade.

I admit that I’ve wondered from time to time if everyone else’s life might have been better if I had died instead of Jillian. It would have been hard on her: she would have had to postpone her surgery from that Wednesday because she would have been making the kind of arrangements that we made for her. I’m sure she would have had good support, but I know that she was not confident in handling the household finances on her own. And then the virus scare still would have come along to take its toll. I suppose she would have had her own regrets to deal with, her own moments of doubt and distress. And while I think the children would probably do better with her than with me — a mother’s love is so much more enveloping and affirming than a father’s love — I would not wish for her to carry even a fraction of the grief that I’ve borne.

So here I am, trying to figure out how to go on with life. I’ve gone through with some of the home improvement projects Jill and I had planned to do — replaced the siding on the house, replaced the old back deck — but for the most part they only remind me that she’s gone. They look great, they’re very well done, and I loathe the thought of enjoying them without her.

I continue to miss her and to wish that she were here, not as a way of denying that she’s gone but simply because of how much I loved her and continue to love her. And in a very selfish way, I wish she were here so that I would never have learned that she had ever been so unhappy with me.

Farewell, my Jillian. I hope you are happy — happier — the happiest you have ever been, or could ever be. And I hope to see you again, and when I do to hear you say that you love me.

___

Previously in the series:

– Unprepared for Regret

– Unprepared for Regret, Part II: Valentine’s Day

– Unprepared for Regret, Part III: Jill’s Last Day

– Unprepared for Regret, Part IV: The Day Jill Died

– Unprepared for Regret, Part V: Six Months Gone

– Unprepared for Regret, Part VI: Our Anniversary

– Unprepared for Regret, Part VII: Hollow Birthday to Me

– Unprepared for Regret, Part VIII: Independence is Overrated

– Unprepared for Regret, Part IX: Forever Autumn?

P.S. If you’ve never read it, you can read Jill’s obituary here.