If you don’t have time to read all of this right now, just know this: Gretchen Rubin’s formulation of the “Four Tendencies” is brilliant, and I highly recommend it as a model for understanding what motivates people — others as well as ourselves. (I do hope you’ll come back and read through this post when you have time, but I’m serious: Look up her work, go to her website, take the quiz to find your tendency, the whole bit.)

So, then, confession time.

I missed a key aspect of motivation when I wrote the original edition of Quality Education that ASQC Quality Press published back in 1993, and then I repeated my error in the revised version I issued a few years ago. Specifically, I wrote about how schools generally offer more external than internal motivators, and how very often those don’t work to keep students interested and on track — a position that I still believe was correct, but I now know to be incomplete.

Why did I make that mistake? Because I didn’t know about the Four Tendencies model. It would have made my entire discussion about motivation much deeper and much more complete. In my defense, Ms. Rubin had not developed her model when I originally wrote Quality Education in the late ’80s. To my chagrin, however, she had written about the tendencies shortly before I put together my new edition, in her book Better Than Before — but I didn’t learn about them until this year.*

As I say, I don’t think what I wrote about motivation was specifically wrong, just that it could have been better. In chapter 27 of the new edition, for instance, while discussing the “psychology” portion of Dr. W. Edwards Deming’s “System of Profound Knowledge,” I wrote of employees:

Management classically has understood enough psychology to stress external motivation, often smothering internal motivation in the process; this is the legacy of B. F. Skinner and the behaviorists. The over-reliance on external factors (for example, pay, awards, time off) to motivate people essentially prostitutes them to the job, and can even rob them of esteem, dignity, and joy in their accomplishments….

Then in chapter 28, applying Deming’s system to education, I wrote of students’ motivations (and couldn’t resist throwing in a Star Trek reference):

Traditional educational psychology, like traditional management practice, has relied on external motivators to entice or coerce students into learning….

In “Miri,” an episode of the original Star Trek series, we find a look at motivation in education. A group of children is gathered together, playing school. One of them holds a hammer; he is the teacher. “What does a teacher say?” asks another of the children. The boy thinks for a moment before speaking, then emphasizes his words with the hammer as he says, “Study, study, study! Or bonk! bonk! bad kids!” That is external motivation.

Internal motivation is Plato sitting at the feet of Socrates. External motivation is the schoolmaster who raps your knuckles with a ruler. Internal motivation is the children coming to see Jesus. And how did he receive them? He took them in his arms and blessed them….

The extremes of the argument over the use of external motivators are poles apart. On one end managers and teachers believe that external motivation (for example, prizes, awards) is good if it helps one person rise above his previous level, no matter how many others may be hurt or demotivated. On the opposite end are those who believe that regardless of the number of people who appear to be helped by external motivators, they should be avoided if they hurt even one individual. I fall closer toward the latter than the former category.

When I wrote that, I never dreamed of juxtaposing internal and external motivators in the way Ms. Rubin does with inner and outer expectations in the Four Tendencies model. (I wish I had.)

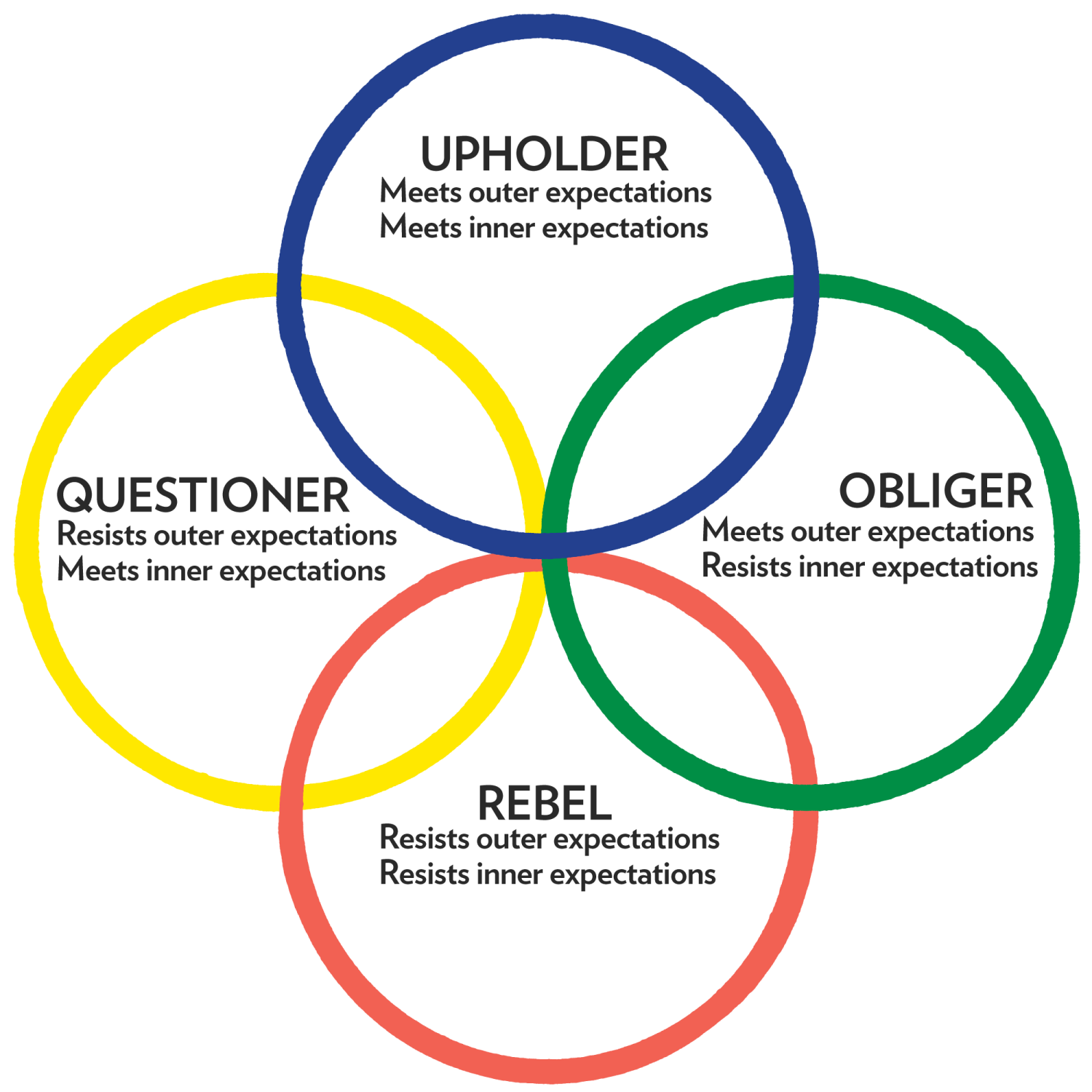

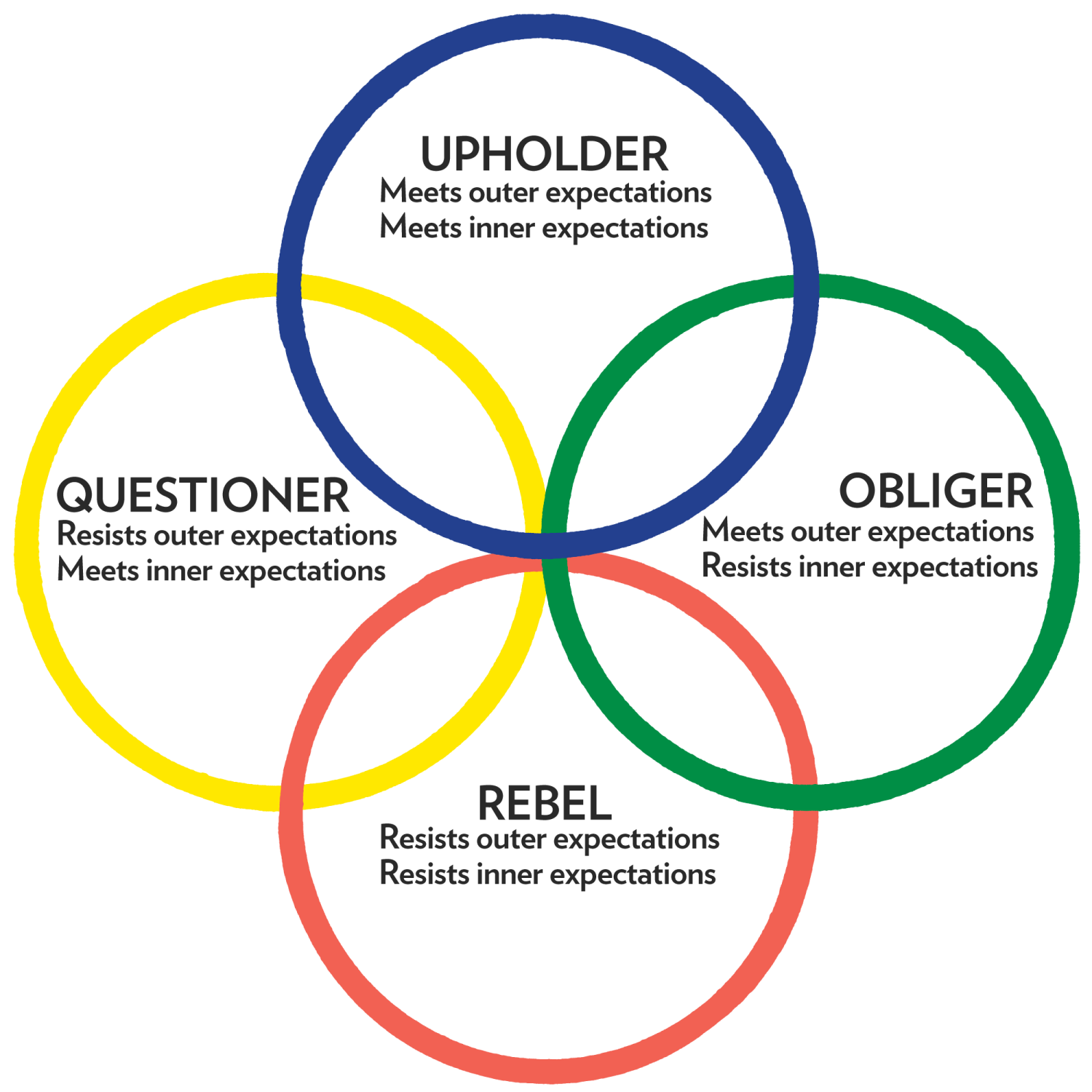

By examining how different people may — or may not! — respond to expectations imposed on them from outside, or the expectations they have of themselves, Ms. Rubin divides all of us into four groups as shown in this graphic from her website:

The Four Tendencies model, developed by Gretchen Rubin.

Applying the Four Tendencies to the classroom, we see that some students respond well to the expectations inherent in the external motivators that many teachers use: they are the Obligers and the Upholders. (Ms. Rubin’s research has shown that Obligers form the largest cohort of the population, and I contend that the prevalence of Obligers is probably a necessary condition to developing a healthy, functioning society.) Those students who respond less well to external motivators are the Questioners and the Rebels. Based on my reading of her work, I now see that my call for discovering and relying more on internal than external motivators — i.e., finding and feeding students’ inner expectations — might work for Questioners, but I effectively missed the Rebel cohort entirely. I did not recognize their outlook at all, so I did not even consider their needs, nor did I try to find ways to help Rebels see the benefits of school and learning.

The aspect of motivation missing from Quality Education, then, is the idea that internal and external expectations and motivators are not a coin to be flipped or an either-or proposition to be considered. We don’t respond in the same way or to the same degree to each. Some of us respond well to both; some respond well to one and not the other; and some do not respond well to either.

Ms. Rubin explains that identifying our tendencies as to how readily we respond to each can help us understand our behavior and our relationships. Not just our personal relationships, but our relationships to institutions such as home and school and church, and our relationships to activities such as work and play and learning.

In sum, I find Ms. Rubin’s approach to be both more elegant and more complete than the simple internal-versus-external approach I took. Not that my approach was completely wrong — I still think what I wrote is sound, and that it’s important to recognize the differences between the types of motivators — but her approach is much better. I highly recommend her work — and I hope my readers will forgive my lack of insight and foresight.

___

*Better Than Before came out in 2015. I only learned about the tendencies a few weeks ago, when I picked up Ms. Rubin’s 2017 book, appropriately titled The Four Tendencies.

by

by