This is the third entry in what has become a series. Links to the first two are at the end.

A few months ago on one of my walks, I started thinking about the idea of a church that would practice radical generosity on a regular basis. I had been reading about charities that were accused of not spending much of their collected funds on their target audiences (for instance, the Wounded Warrior Project apparently spends much more on its television commercials and executive salaries than it does to actually help wounded veterans), and I began to wonder about churches and their use of collected funds.

I’ve been active in many different churches over the years, in mainline denominations (e.g., Baptist, Presbyterian), in nondenominational churches, and in what I liked to call the “multi-denominational” environment of the chapels on various Air Force bases. I’ve visited many more churches, from the East Coast to the West Coast, many places in between, and even a few churches in other countries. In comparing all those churches, it should come as no surprise that some of the churches did more to serve the needy than others.

This past year in particular, I began to suspect that the donations we’ve made to local rescue missions did more to directly help the needy than the donations we’ve ever made to a local church, of whatever type. Why? Because the local churches’ receipts went almost entirely to cover their own operating expenses, and those expenses were not usually devoted to serving the needy. So I began to think about how a church might work if serving the less fortunate was its primary purpose for being.

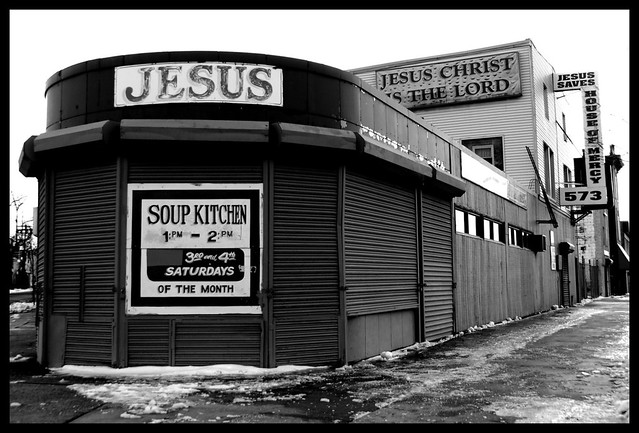

Serving the needy, two Saturdays out of the month. (Image: “Jesus Feeds the Hungry (5 of 12),” by Tony Fischer, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

Gradually a picture formed in my head of a church — I called it The Gift Church — that would spend more money on helping others than it spent on itself. I outlined that purpose and the guiding principle behind it in the previous two posts on this subject. If you missed those installments, here’s how I put it:

Purpose. The purpose of the Church is to advance the Gospel of Jesus Christ through service to the community and the world. The Church has been given gifts that are meant to be shared.

Central Tenet. Believing that the Lord Jesus Christ’s declaration is true (as reported by Paul the Apostle to the Ephesian church leaders in Acts 20:35), that it is indeed more blessed to give than it is to receive, the Church shall devote more of its monetary resources to serving the needy than it does to its own internal obligations, needs or desires.

Guiding Principle. In the same way that the Lord Jesus Christ did not select disciples so that they could serve only one another or that He could serve only them, the Church does not exist so its members can serve only one another or keep His blessings to themselves. If the Church ceases to serve others, or serves itself to the exclusion of others, it shall not have fulfilled its purpose, because the observation that “where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” (Matthew 6:21, and especially Luke 12:33-4) can be understood to apply to the corporate Church as well as to individual believers, and so can the Lord’s teaching that service to the poor and downtrodden is, in effect, service to Him (Matthew 25:31-46).

How might that work in practice? First, I should admit that it might not. But if it could, I envision a few elements of its operating as:

- Regular Charitable Support. The Church would donate regularly to organized charities that directly serve the needy (and/or give money directly to people in need), such that for every dollar the church spent on itself, it would spend a little more than a dollar on the needy. If the Church spent $100 on, say, office supplies, it would then donate $101 to charitable work, and so forth. The Church would have to keep its own expenses reasonable in order for its receipts to cover its own needs and its charitable donations.

- At a Minimum, a Tithe. If the Church kept its expenses very low in relation to its receipts, it could conceivably retain a great deal of money as a surplus. That would not be bad, as Scripture encourages frugality and planning for lean times — and once some of the surplus was spent on church expenses, a charitable donation would still have to be made. However, it would seem appropriate for the Church to donate at least a tenth of its total receipts, regardless of its expenses.

- Meeting Needs As They Arise. At any time, members may become aware of needs in the community or the wider world, so any member of the Church could propose a charity (or person) to receive a donation from the Church. The decision-making authority, however, would rest with the assembly of Deacons since that’s why the office of deacon was established.

- Meeting a Mix of Needs. To keep its focus from becoming too narrow, the Church would distribute its donations to a variety of local and non-local charities. The actual mix might vary from year to year, but the Church would give more than a fourth of its donations to non-local charities. Of the remainder that stayed in the local area, the Church would ensure that no more than a fourth of its donations directly benefited its own needy members. But even a balance like that could be changed if the Elders and Deacons became aware of specific needs that the Church could help meet.

- Charitable Missions. To maintain its focus on helping the needy, the Church would only count donations to missions as “charitable” if those missions themselves involved direct service to needy people.

- Provisions for Large Donations or Expenses. From time to time, starting in the early church, people have liquidated property and given the proceeds to the church; most churches could receive such a large gift easily, but under the “tithe” provision above a large gift could stress The Gift Church’s ability to live up to its own central tenet if it did not have funds on hand to donate one-tenth of the gift’s value to charity. Likewise, sometimes a church is faced with a large expense for which making a more-than-matching lump-sum donation would be impractical. In these events, the Church would have the leeway to make its charitable donations in installments.

- Reporting and Accountability. The Elders would report the cumulative receipts, expenses, and donations to the congregation at intervals throughout the year, and provide a detailed report at year’s end. In this way, the members could be sure the Church was living up to its stated purpose — and if for some reason the Church failed to do so, could take corrective action.

Do you think a church like that might be able to function for very long?

Would it be able to keep its expenses reasonable and encourage its members to give sufficiently to cover the expenses and its charitable work?

I don’t know.

What I believe is this: When Scripture tells us to “bring the whole tithe into the storehouse” (Malachi 3:10), the implication is not that all the food in the storehouse is intended to stay there. It is intended for the Levites and the needs of the Temple, yes, but not for the worshipers. And any excess is not meant to be left in the storehouse to rot.

But maybe I’m the only person who thinks that.

___

Previously in this series:

The Church I’d Like to Start: A Church that GIVES

The Gift Church: Its Guiding Principle