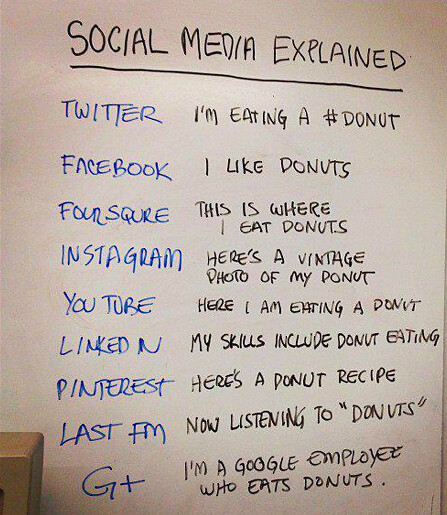

So, how many social media sites are you on these days?

I ask because I’ve been watching with some amusement the mass exodus from X/Twitter to Bluesky. A great many folks on Facebook have announced their transition from the one with the blue bird logo to the one with the blue butterfly logo, often with snarky commentary about Mr. Musk’s management of the former and/or the results of recent election. (Alas, some of the commentary is more hateful than snarky.)

I’m still on X/Twitter, but the other day I set up a Bluesky account to see what it’s all about. As my first post, I submitted some verse:

Bluesky Beckoning

I see blue sky outside my window

Behind the few remaining leaves

Shaking as the autumn wind blows

And the smiling sun deceives me

Into thinking that it’s warm out

Despite the trees becoming bare–

Still, I’ll go stumbling down the scenic route

In the invigorating air

This makes the sixth social media site I’m on, which is probably three too many. In rough order of how much time I spend on them, I’m on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, MeWe, and Bluesky. I was on Google+ while it lasted, though I didn’t use it much, and still have a Gab account which I haven’t looked at in ages. That’s in addition to bulletin boards like Baen’s Bar and Discord; sites that are considered social media but I don’t use as such, like YouTube; and things I’m not sure how to categorize, like Substack. Imagine if I were also on TikTok and Threads and Reddit and Snapchat and Pinterest and Tumblr and … what did I miss? I’m sure I missed some.

It makes me long for a treaty on the nonproliferation of social media.

(Image: “Social Media Icons With Paint Splash Effect,” by Lewis Ogden, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

Which brings me back to the X/Twitter-to-Bluesky exodus.

From what I’ve seen, the majority of people posting about moving completely from one site to the other seem wistful, as if remembering X/Twitter as some idyllic playground where they waltzed carefree among sweet-smelling flowers of approval and likemindedness. And perhaps for them it was just so! Now that others have gained verbal ground on them, though, with arguments they consider distasteful and attitudes and opinions of which they disapprove, they have packed up their toys and moved to another playground.

Now, I’m all for spending time with friendly people rather than enduring hostility. But that Bluesky playground has its own unsavoriness. Much of the posting — and this may be because it’s still so new to so many people — expresses relief that they found a new playground, albeit often with no small amount of disdain for those who would choose to stay behind. Some of the sneering and condescension is amusing, though not when it seems to slide from simple dislike into snobbery and hatefulness.

I don’t know how comfortable all the Bluesky immigrants should be. One day, something may spark an exodus from Bluesky to some new platform yet to be imagined. Sites come and go — MySpace, anyone? — and some people will always be looking for the next, better thing.

I expect the end result will be more societal fragmentation, as the echo chambers resound in chorus and the political bubbles thicken and calcify by us-versus-them rhetoric, rather than minds meeting in ways that help us understand one another — even if we choose not to appreciate one another. But because I can be a glutton for punishment and believe that bridging gaps between people is important, I will stand in the middle, dipping my toes into each pond now and again, ready to engage with anyone on either side who is willing to discuss, debate, or even argue in good faith and civility.

Let me know if you’d like to stand with me.

___

For other musings and oddball ideas, see

– My latest release, also with some gap-bridging implications, A Church More Like Christ

– My other recent release! Elements of War

– My Amazon Page or Bandcamp Page, or subscribe to my newsletter

by

by