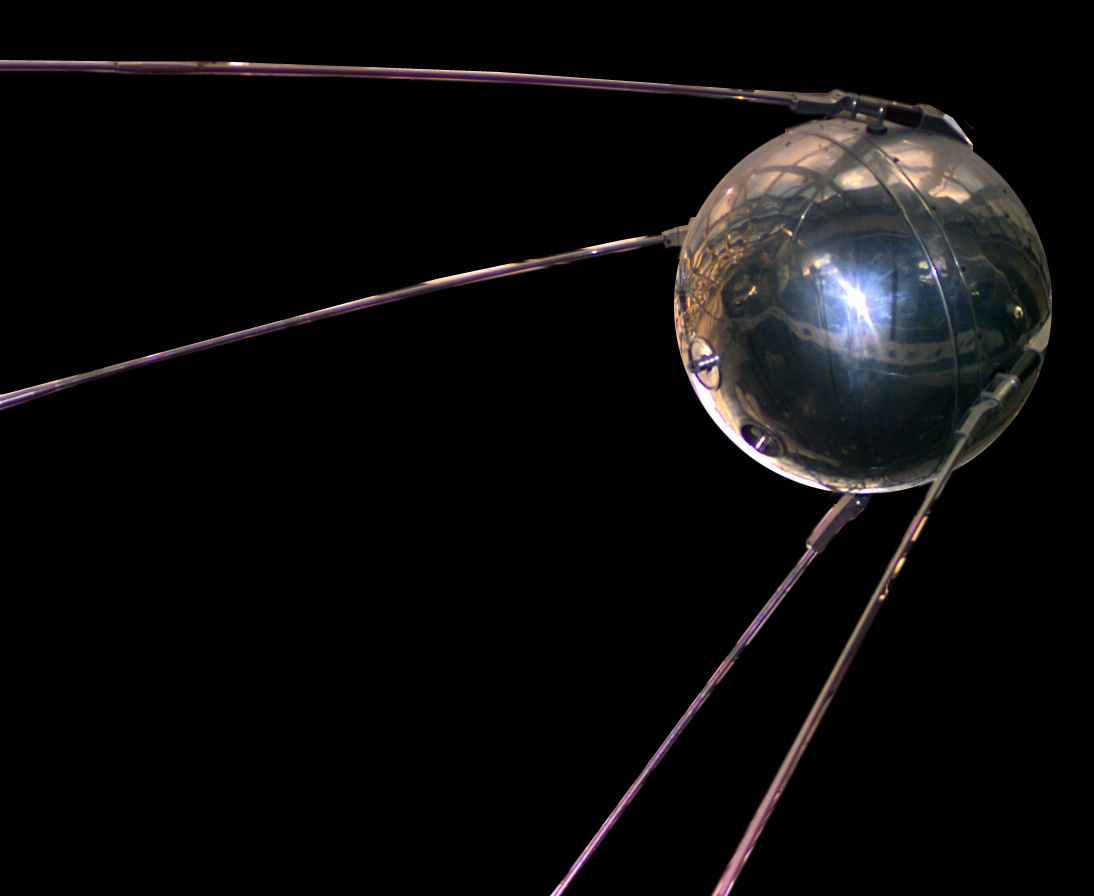

Fifty-five years ago today — October 4, 1957 — the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome.

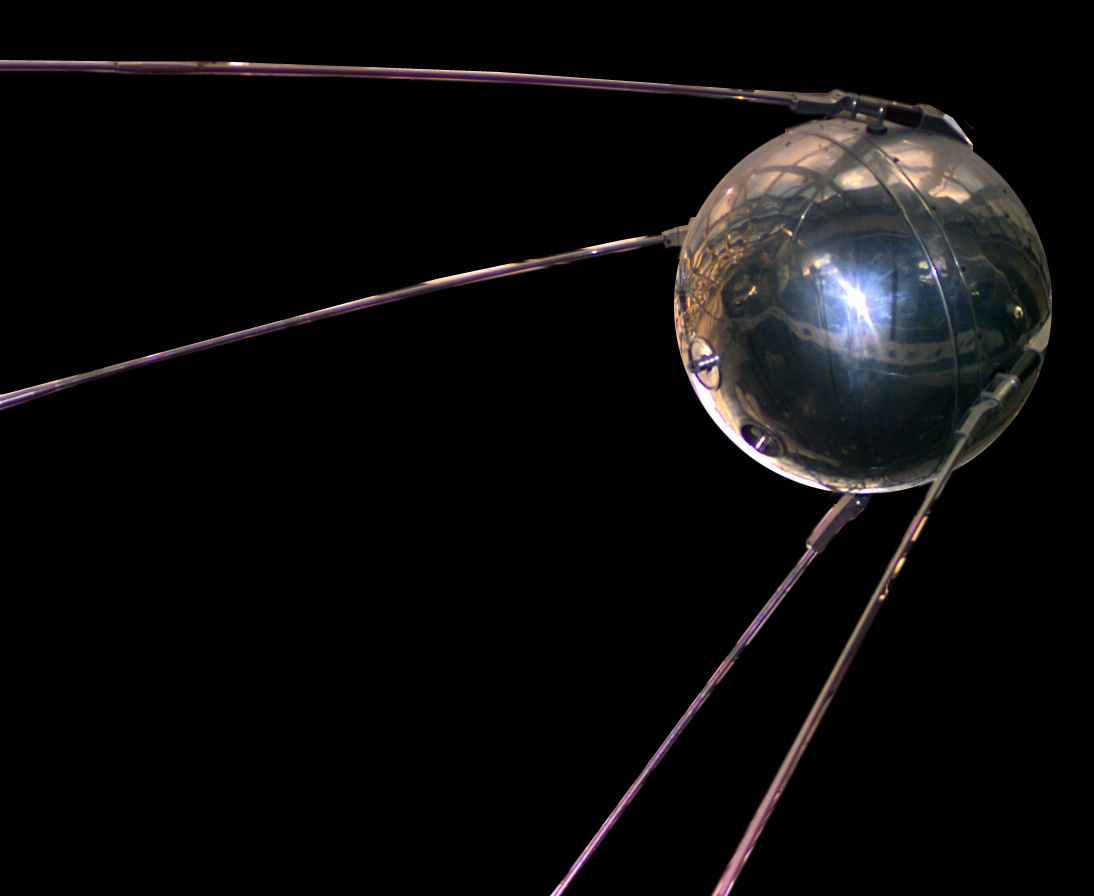

(Sputnik. Image from the National Space Science Data Center.)

Anyone with an interest in space history learns early on that Sputnik 1 was the first successful artificial satellite. It was actually the first in a series launched by the USSR for the International Geophysical Year. The name Sputnik means “companion,” in the sense that a satellite orbiting a planet is its celestial companion.

Sputnik 1 was built as a pressurized aluminum sphere containing radio transmitters and instruments. It collected data on atmospheric density at high altitude and the effects of the ionosphere on radio transmissions.

Since the sphere was filled with nitrogen under pressure, Sputnik 1 provided the first opportunity for meteoroid detection (no such events were reported), since losses in internal pressure due to meteoroid penetration of the outer surface would have been evident in the temperature data. The satellite transmitters operated for three weeks, until the on-board chemical batteries failed, and were monitored with intense interest around the world. The orbit of the then inactive satellite was later observed optically to decay 92 days after launch (January 4, 1958) after having completed about 1400 orbits of the Earth over a cumulative distance traveled of 70 million kilometers.

To celebrate the 40th anniversary of the launch of Sputnik 1, in 1997 the Russians launched a miniature replica named Sputnik Jr. aboard a Progress resupply ship bound for the Mir space station. Built by French and Russian students, Sputnik Jr. was released from the Mir station on November 3, 1997.

One interesting note about the original Sputnik 1 is that the satellite was not the only part of the package to reach orbit. Its rocket booster also reached orbit, and because of its larger size was actually more visible in the night sky than the highly polished satellite.

Students of space history know that Sputnik 1’s presence in the sky caused an uproar and led to a frenzy of space-related activity. As the brief essay “Sputnik and the Crisis That Followed” puts it,

As news of the Soviet accomplishment quickly spread by radio and television reports, untold millions climbed onto rooftops, ventured into city parks, or ambled out to dark backyards, all scanning the heavens for a brief glimpse of a rapidly moving star. It was a communal experience that would later become known simply as “Sputnik Night.”

…. The American response to Sputnik bordered almost on panic. The Chicago Daily News declared that if the Soviets “could deliver a 184-pound ‘moon’ into a predetermined pattern 560 miles out into space, the day is not far distant when they could deliver a death-dealing warhead onto a predetermined target almost anywhere on the earth’s surface.” Newsweek magazine dolefully predicted that several dozen Sputniks equipped with nuclear bombs could “spew their lethal fallout over the U.S. and Europe.”

…. Thus, the United States and the Soviet Union began a duel for control of the heavens, the so-called “Space Race” that consumed both nations for the next 11 years, ending only when American astronauts first set foot on the Moon on July 20, 1969.

On this date in history, the starting gun sounded for the Space Race. The first leg of that race may have ended, but it is at least a relay if not a marathon. The longer race has barely begun.

by

by