A few weeks ago I posted about Gretchen Rubin’s “Four Tendencies” model,* and specifically how it revealed a mistake I made in my book on education** — not an error of fact, but an error of omission due to my own failure of imagination.

Since then I’ve been thinking about the Four Tendencies as they might apply to characterization in fiction.

To recap, Ms. Rubin identified four categories into which we sift ourselves according to how we respond to expectations — both our own, inner expectations, and the expectations we perceive that others have for us. Some of us readily meet expectations, and others of us resist expectations, generally as follows:

- Upholders: Meet both outer and inner expectations

- Obligers: Meet outer expectations, but resist inner expectations

- Questioners: Resist outer expectations, but meet inner expectations

- Rebels: Resist both outer and inner expectations

Like many such schemes, this one has its strengths and weaknesses (e.g., I wish she had explored in more depth the areas where the tendencies overlap), but I find that it has some excellent insights into our choices and behaviors. As statistician George Box said, “All models are wrong. Some models are useful,” and the Four Tendencies is a quite useful model.

So how can this model apply to writing fictional characters?

(Image: “Writer’s Block I,” by Drew Coffman, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

I think anything that helps us understand that mysterious thing called “human nature” is useful in creating characters who readers will find interesting and believable, let alone relatable and sympathetic. And understanding the Four Tendencies has the potential to make a big difference in writing characters who have clear motivations and consistent reactions to the expectations of the other characters around them.

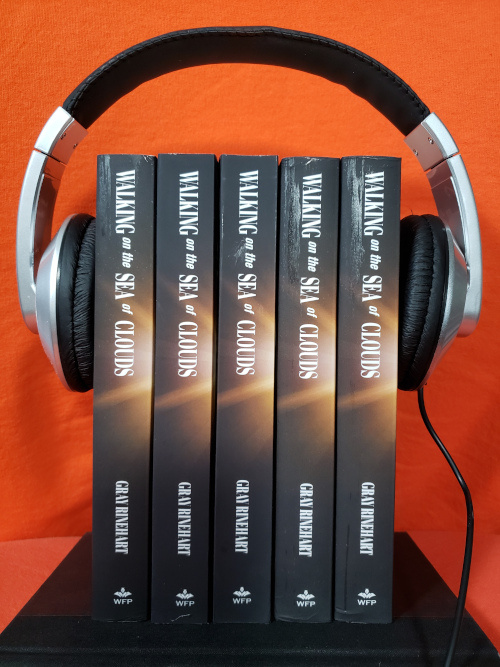

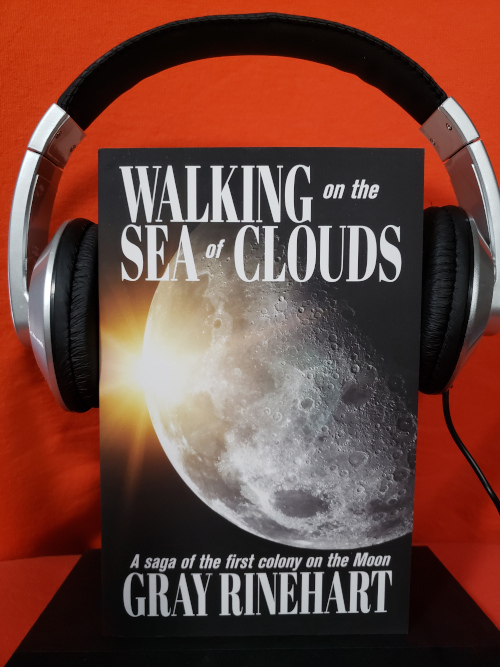

When I think about the main characters in Walking on the Sea of Clouds (now available in audiobook***), for instance, I think Stormie Pastorelli fits the pattern of an Upholder. She’s driven to succeed, and to help the lunar colony survive and thrive, with a strong “by-the-book” approach and a heavy insistence on living up to her high expectations of herself. I think her husband Frank, on the other hand, is an Obliger: he is ready and willing to do things that other people expect of him, even sometimes at the expense of his own well-being.

Of the other main characters in the novel, Barbara Richards is probably also an Obliger, and that makes her struggle about whether to stay at the lunar colony realistic. (It makes sense to me for two of the main characters to have that tendency, since Ms. Rubin points out that Obligers form the most prevalent tendency in society; honestly, I don’t think society would function if Obligers weren’t the largest group.) I think Barbara’s husband Van, though, is primarily a Questioner — perhaps with a bit of Rebel thrown in.

If you’ve read Walking on the Sea of Clouds, what do you think? Does that assessment sound right to you? How do you think I did in keeping their characteristic tendencies consistent?

If you’re a writer, do you think the Four Tendencies might help you better understand the personalities of your main characters, in order to keep their characterizations consistent? I’d be interested to know your thoughts.

As for me, I’m working on a fantasy novel these days, and I’m keeping the Four Tendencies in mind as I try to figure out my characters’ motivations and their feelings about the expectations placed on them. I hope I’ll be able to make them seem realistic! But that, in the end, will be decided by the readers.

___

*Full (and somewhat unwieldy) title: The Four Tendencies: The Indispensable Personality Profiles That Reveal How to Make Your Life Better (and Other People’s Lives Better, Too).

**Quality Education: Why It Matters, and How to Structure the System to Sustain It (a fairly unwieldy title of my own).

***Reminder for anyone who missed the announcement: I’m running a series of giveaways for Audible downloads of the Walking on the Sea of Clouds audiobook. Sign up at this link!

by

by