According to author Christina Rasmussen, “Healing only lives in celebrating the lives of the ones we have lost, not how they died.” That may be true, but this recollection is no celebration….

Five months ago today, my wife of thirty-four years, Jill Rinehart, died. A month ago, I wrote about her last day, which ended this way:

I climbed in bed after I brushed my teeth, and — as I did every night — snuggled up with her a little bit while she fast-forwarded through a [television] commercial. She told me that the medicine she’d gotten, which she’d applied around her nostrils as instructed, made her breath feel “hot.” It bothered her, but it was supposed to be important so she was enduring it.

When the show was over, she said she was a little bit hungry and wanted a snack. But the puppy was asleep on the floor on her side of the bed, so instead of getting out that way she rolled over top of me. She lay on top of me for a second, and we smiled at each other, gave each other a hug and a kiss, and said goodnight. She got out on my side and turned off the light as she left.

That was the last time I saw her alive.

The medicine Jill had applied to her nose was some sort of antibacterial treatment that she was supposed to use until her surgery (coming up in five days). As I understood, it was supposed to reduce the risk of her getting sick prior to the surgery and to reduce the risk of infection. Why it made her breath feel hot, I don’t know.

It was not unusual for me to fall asleep before her. It was unusual for her to still be up before I went to sleep. It turned out that in addition to getting a snack, she also cleaned up the sculpture project she was going to teach the next day, and put the examples she had made in her studio with her art bag, ready to go. Then she came back to bed, but I was already hooked up to my CPAP machine and sleeping soundly.

I woke up to her sniffling and snorting — or so it seemed; I remember only one big snort — as if she had bad postnasal drip. The clock showed that it was midnight. She settled back down, and I thought about the medicine and guessed that it had caused her nose to run.

But almost immediately the puppy came around to my side and started trying to jump up on the bed. I told him everything would be okay and to go back to his bed. He did.

I was perhaps half-awake at that point, and expected Jill to get up (or at least sit up) to blow her nose. When she didn’t, I lay there for a moment wondering if she was okay. I actually wondered briefly if she had just died: I hate to admit that, because in that instant I didn’t immediately reach out to check on her. Why? Because she hated to be awakened in the middle of the night. (She always had trouble getting back to sleep.) So I lay there for another moment — I don’t really know how long, it might have been five seconds or ten or twenty, I have no idea — trying to discern if she was okay.

Finally, I reached out and touched her shoulder. And she did not move.

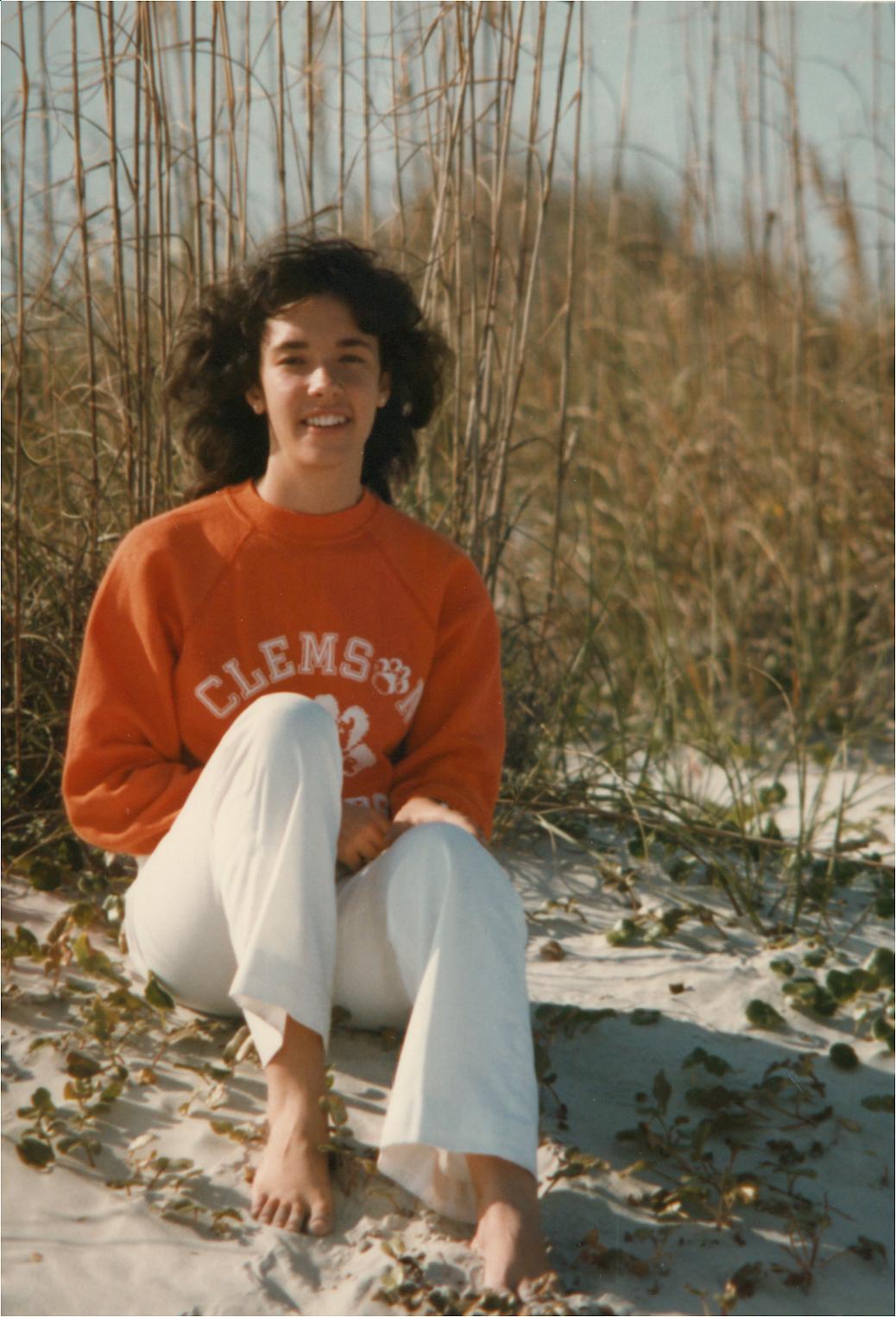

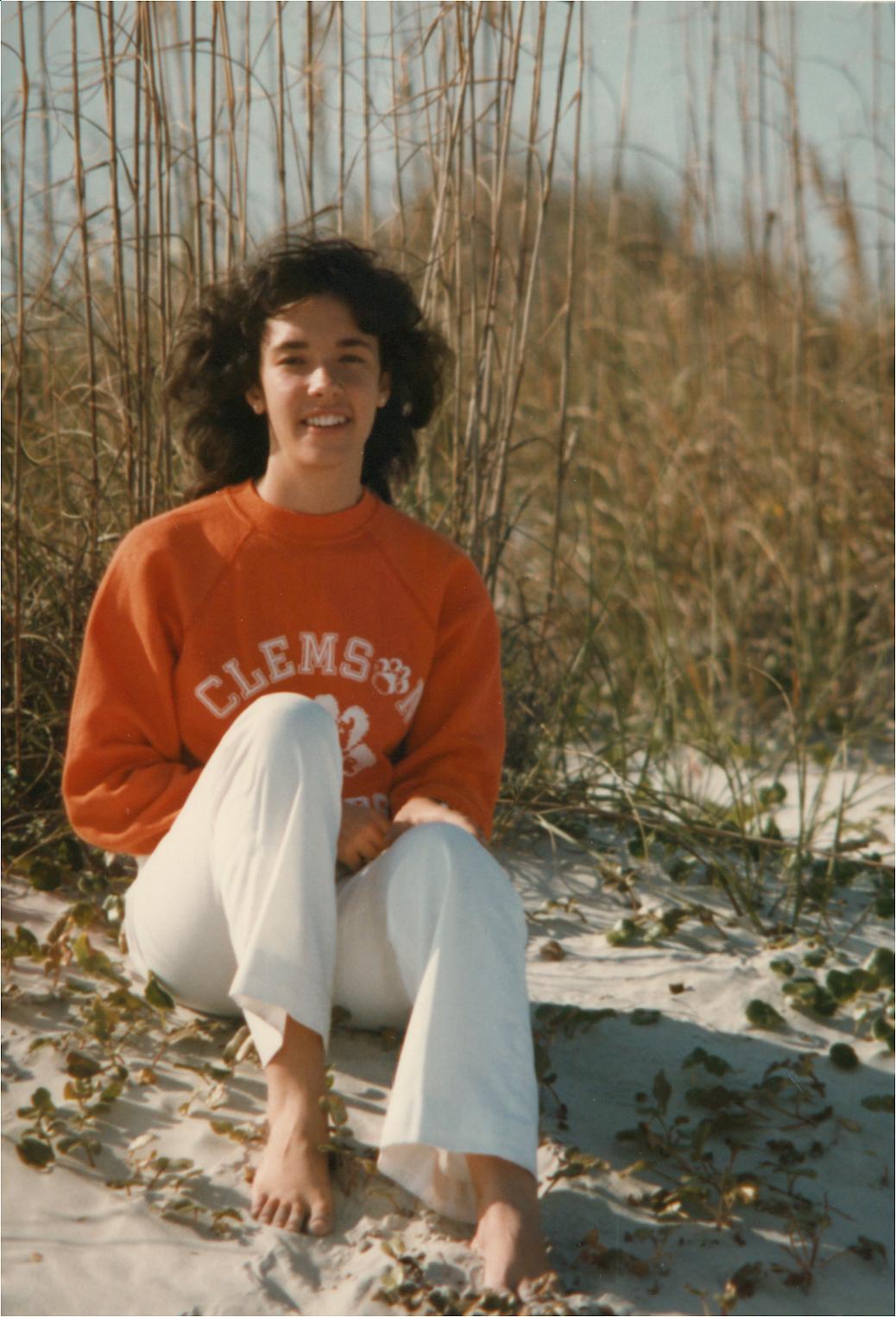

(One of my favorite pictures of Jill, taken in 1982 at North Litchfield Beach, SC, when she was oh-so-alive.)

The next few minutes blur together in my memory. I shook her, I called out her name, she still didn’t move and she didn’t respond. I knew from CPR training years ago that the most important thing to do was to activate the emergency medical system, so I picked up the phone and turned on the light — but that handset had no power so I had to run into my office and grab another one. I called 911 and put the speaker on. Then, because I know you can’t do CPR on a soft surface, I pulled her onto the floor as expeditiously as I could without hurting her. But the way our bedroom is situated, there is hardly any space between the bed and the wall, so I had to pull her farther into the room. Finally I started CPR, hardly able to speak to the operator or to see what I was doing through my own tears.

A few minutes later (again, I don’t know how long), the dispatcher told me that the responders were approaching the house and asked if the front door was unlocked. It wasn’t, of course, so I had to run downstairs to unlock it. At that point I took notice of the puppy. He must have been pacing around in the room while I was moving Jill and starting CPR, but he had never gotten in the way. Now, he ran downstairs with me and I put him in his crate. I unlocked and opened the front door and ran back upstairs to keep doing CPR.

But it didn’t work.

The next thing I remember, EMTs were in the room, shoving the end of the bed out of the way and pulling me back so they could start trying to help her. I think one of them escorted me out and led me down the stairs and asked if there was anyone I needed to call. At least, I know I ended up downstairs, sitting on the floor in my underwear by the dog’s crate, with my cell phone.

Both of our children live near us, so I called them and they came to the house as quickly as they could. By the time they got there, between the EMTs and police there were probably six or eight or more people in the house. The police were very polite and professional, as were the medical technicians. Stephanie and Christopher helped me answer questions, and at one point I had to go upstairs to show the detective the medications that Jill had on hand. Several EMTs were surrounding her at the time, and I could not see — perhaps because I didn’t want to — what they were doing to her. The young-uns and I answered questions about her upcoming surgery, and probably other things that I don’t remember.

I spent most of my time sitting on the living room floor, petting the pup through the bars of the crate. I occasionally heard the whine of the defibrillator the EMTs had brought in. I couldn’t make out what they said to one another upstairs, and maybe I wouldn’t have wanted to. I guess it was around 1:30 in the morning when they gave up because they weren’t able to get Jill’s heart to restart and keep a steady beat. Since she was scheduled for heart surgery in a few days, they made the assumption that she had died of a heart attack. The police said there was probably no need to do an autopsy, and the children and I agreed.

Next thing, we were being asked what funeral home we wanted to use — a question I never envisioned being asked. We picked the only funeral home I had ever been to in Cary, where members of our church had been taken care of, and I think the police detective actually called them. I don’t remember. But some time later, though still in the early morning, two fellows from the funeral home showed up. After a little consultation, they took her away. Because of the difficult arrangement of the stairs in our house, it was not easy for them to bring her downstairs and get her ready to go. The children moved into the kitchen, so they wouldn’t have to see, and I can’t blame them. The only saving grace is that the same faulty memory that keeps me from being able to recall really good things in vivid detail, keeps me from being able to remember much of the details of watching them take her out.

The rest of the day passed in almost as much of a blur as the early morning hours. We called family and friends, church people came over to offer what help they could, Christopher and I went to the funeral home to make the initial arrangements, and my sister drove in from Southport to stay with me. Things were complicated a little bit by the fact that the furnace stopped working that night, and I had to call to have it fixed (which the company was only able to do temporarily).

Since this post is supposed to be about the day she died, and is already quite long, I won’t go into detail about all the activities that went on before Jill’s memorial service a week later. Again, they all blend together in my mind: asking friends to play music or to read Scripture, setting up the memorial fund at the South Carolina Botanical Garden, and so forth. But I need to record one key event from that week, because it was quite possibly the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

In the middle of the week — I don’t remember now which day it was — I had to identify Jill before she was cremated.

I had to go see her in the funeral home.

I went alone, so the children would not have to remember her that way.

The hardest thing I’d ever done was to walk into that room, knowing that she was in there. I don’t remember how long I stayed — an hour, I’d guess — talking to her, holding her far-too-cold hand, kissing her beautiful face and her lovely hands. But, as it turned out, in the end walking into that room was only the second hardest thing for me. Because even though I knew that it wasn’t really her; that she was gone; that her spirit, her soul, was far away; by far the hardest thing I’ve ever done was to walk out of that room again, to leave her alone there. It still breaks my heart to think of it.

___

In terms of being unprepared for regret, my biggest regret is my hesitation: my failure to act quickly enough to be able to help her. My doctor and friends in the medical field have told me that it probably wouldn’t have made a difference, but I carry a significant amount of guilt and in a very real way I hate myself for every second that I hesitated. My greatest fear is that she might have wondered, for even a fraction of an instant, why I wasn’t helping her.

Another thing I regret is that I did not remember that Jill was an organ donor, so the technicians could take that into account. I also didn’t remember that both she and I have living wills and she didn’t wish to be resuscitated, but in that moment I could do nothing but try — even though I was too late.

I also regret now not having an autopsy performed, because according to Jill’s cardiologist she could not have had a heart attack. She had gone through an echocardiogram and had a complete workup in order to verify that she was a good candidate for the mitral valve repair surgery, and the surgeon told me that she had no coronary artery disease. Aside from the one problematic valve, her heart was completely healthy. As a result, we believe she had a seizure, brought on by the stress she was under of the upcoming surgery and recovery. (She had had a seizure four years prior when she was under some stress, so it’s at least possible.) I understand that an autopsy would not have conclusively proven a seizure, and may not have told us what happened. Some things, perhaps, we can never know.

One final note: After her first seizure — which was almost four years to the day before she died — Jill told me that as she lost consciousness she thought she was about to die. She said she thought something like, “If this is my time, and this is how I’m supposed to go, I’m okay with that.” As difficult as it was to lose her the way we did, I know that falling asleep in our bed and not waking up was a far better way to go than many other ways she might have died. I can only hope — and, oh God, how fervently I hope, I hope, I hope — that her last thought, in her last moment, was peaceful and that she was okay.

___

Previously in the series:

– Unprepared for Regret

– Unprepared for Regret, Part II: Valentine’s Day

– Unprepared for Regret, Part III: Jill’s Last Day

P.S. If you’re interested, you can read Jill’s obituary here.

by

by