Authors: Here’s a lesson in how not to respond to rejection.

As the “Slushmaster General” for Baen Books, I have the unenviable task of sending out rejection letters. I don’t particularly like it — I know well how it feels to be on the receiving end — but I do it. And because we get a lot of submissions, I send out a lot of rejections.

This applies to more than just publishing! (Image: “rejection,” by Topher McCulloch, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

Now, Baen Books could go the route some publishers and literary agents have gone and simply not respond at all if we’re not interested. We haven’t done that, though, and I don’t believe we ever will. As I tell people at convention panels and workshops, as an author myself I like to make sure that we treat every submission the way I hope other publishers are treating my submissions.

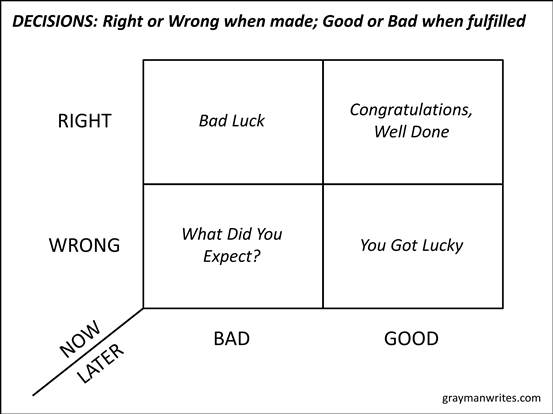

Which brings me to today’s lesson: keep your expectations realistic, and think twice before complaining.

Our guidelines note that we typically respond to new submissions within nine to twelve months, though we’ve gotten to the point that it’s usually six to nine. Why so long? Because in any given month we receive upwards of 120 submissions, and while there are always a few I can respond to quickly — e.g., short stories instead of novels; memoirs or poetry or children’s books or other things we just don’t publish — it takes time to look at each submission and judge it on the merits.

Anyway, last week I sent an author a rejection and the author e-mailed back,

This book has been published for months! You should try and better manage your time with submissions.

Hmmm.

Published, you say? Meaning … not available anymore? Meaning you could have told us that, and saved us the trouble of considering it, but didn’t? Or meaning that you expected us to respond in a few weeks instead of the several months it usually takes?

And published “for months,” you say? (With an exclamation point, no less.) Publication cycles usually take many months to over a year, depending on the publisher’s editorial, art, and production schedules … so was your book already accepted somewhere else before you submitted it?

I decided this response warranted a little investigation. I know when the book was submitted to us and when I responded, and since I have this fancy tool called the “Internet” — maybe you have it, too — I could find out exactly when that book was published. Let’s check the record, shall we?

- Submitted 3 February 2016

- Rejected 23 July 2016 (elapsed time, 171 days — c. 5.6 months)

- Published 1 April 2016 (58 days after submission)

Hmmm.

So, you published (self-published, if I read the Amazon listing correctly) your book less than two months after submitting it but didn’t withdraw it from our consideration? And then when we respond in a little over half the time we advertise you decide to berate us for not responding sooner?

Oh, aspiring author out in Internetland, I trust that you, and most other people reading this post, would know not to do this. But, just in case, let me be clear: don’t do this.

Know what to expect when you submit something; specifically, bear in mind that your submission is one of many. (We will get to it. If you’re worried that we might have lost it, just ask.) Be professional and courteous enough to withdraw your submission if you decide to publish elsewhere. And when we respond, if you think it took longer than it should have, be sure your expectation was realistic before you start complaining about our time management.

Otherwise, your complaint might end up as a prompt for a blog post.