(Another in the continuing “Monday Morning Insight” series of quotes to start the week.)

That title is not a joke.

Before we get to it, let me admit my ignorance: I did not know, until I started looking for this week’s quote, that Cyrano de Bergerac — the real-life de Bergerac — was one of the earliest science fiction authors.

Today is Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac’s birthday (6 March 1619 – 28 July 1655), and it turns out he was not just a character in a story who helped his friend woo the woman he really loved. That was made up by Edmond Rostand, whereas in real life de Bergerac was a French soldier, a playwright, and — as it turns out — a science fiction novelist.

He actually wrote two science fiction novels, both of which were published posthumously: L’Autre Monde: ou les États et Empires de la Lune (The Other World: or the States and Empires of the Moon, 1657), and Les États et Empires du Soleil (The States and Empires of the Sun, 1662). The first was published as the “Comical History” of the States and Empires of the Moon, thanks to being renamed by Henry Le Bret, de Bergerac’s friend, who also excised material he considered objectionable.

But let’s get to the quotes….

This bit in L’Autre Monde may come across as comical to us, until we consider that de Bergerac wrote it over 300 years before the Apollo program made the Moon’s nature more familiar to more people:

“I think the Moon is a world like this one, and the Earth is its moon.”

My friends greeted this with a burst of laughter. “And maybe,” I told them, “someone on the Moon is even now making fun of someone else who says that our globe is a world.”

I read some foreshadowing of H.G. Wells in there, as I think of how The War of the Worlds opens. We know so much now about our Solar system that we did not know then. (And as one whose forthcoming debut novel concerns the early days of a lunar colony, I confess a bit of jealousy: it might have made my own writing easier if I hadn’t had to try so hard to make the fiction part live up to some real science.)

But de Bergerac did not limit his imagination just to the Moon. Consider that he wrote this in the 1650s:

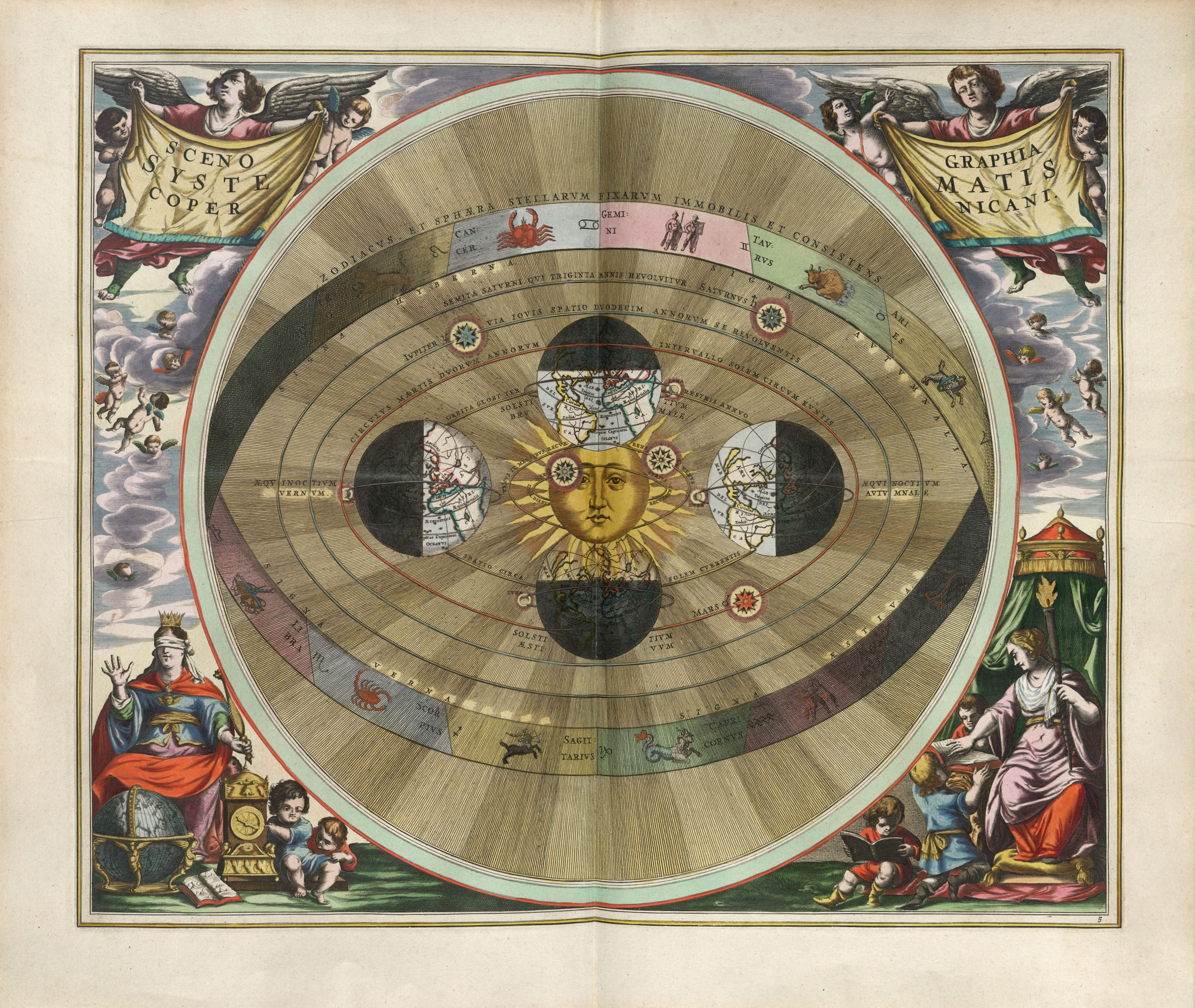

I think the planets are worlds revolving around the sun and that the fixed stars are also suns that have planets revolving around them. We can’t see those worlds from here because they are so small and because the light they reflect cannot reach us. How can one honestly think that such spacious globes are only large, deserted fields? And that our world was made to lord it over all of them just because a dozen or so vain wretches like us happen to be crawling around on it? Do people really think that because the sun gives us light every day and year, it was made only to keep us from bumping into walls? No, no, this visible god gives light to man by accident, as a king’s torch accidentally shines upon a working man or burglar passing in the street.

A representation of the Copernican model of the Solar System. (Image: “Harmonia macrocosmica …,” by Andreas Cellarius, 1661, from Wikimedia Commons.)

What would de Bergerac have made of our efforts to peer into the depths of space, by which we have found dozens of exoplanets — planets orbiting distant stars? I think he would be pleased, and perhaps a little disappointed that we had not yet found ways to reach them.

I think de Bergerac’s literary achievement is all the more impressive when we put him and his novels in relation to other science and literary luminaries:

- Copernicus (1473-1543): formulated the heliocentric view of the Solar system

- Galileo (1564-1642): confirmed by observation the Copernican view

- Johannes Kepler (1571-1630): in addition to formulating the laws of orbital mechanics, also wrote in 1608 what some consider the very first work of science fiction, Somnium (The Dream), published in 1634

- Francis Godwin (1562-1633): Anglican bishop, wrote The Man in the Moone, published in 1638

- de Bergerac (1619-1655): The Other World: or the States and Empires of the Moon, 1657; and The States and Empires of the Sun, 1662

- Voltaire (1694-1778): in addition to his philosophical works, wrote a short story about an alien visitor to the Earth, Micromégas, 1752

- Mary Shelley (1797-1851): Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus, 1818

- Jules Verne (1828-1905): From the Earth to the Moon, 1865

I had been under the impression that Frankenstein was the first science fiction novel, and had no idea that so many authors had explored the notion of space travel two centuries before Verne’s classic was published. Maybe you knew all that, and knew that Cyrano de Bergerac was more than just a character in a story. I’m glad I know it now, and probably shouldn’t have been surprised to learn just how far back science fiction started — just as authors today extrapolate from the findings of current science, why shouldn’t authors have done so 350 years ago?

My dad is fond of saying, “Learn something new every day.” Maybe this can qualify as your “something new” for today. But even if it doesn’t, I hope you learn something new today, and all this week!

by

by