(Another in the continuing series of quotes to start the week.)

It may do little to improve your Monday to remind you that tonight is the first Presidential debate of the 2016 election. Here’s something to think about as the debate looms, from a letter written this week in 1820 by Thomas Jefferson:

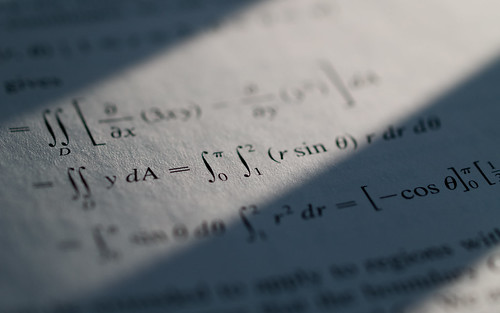

I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education. This is the true corrective of abuses of constitutional power.

A photographer spotted this bus in Australia. I feel as if I’m riding it to the end of the line. (Image: “undecided,” by Vanessa Pike-Russell, on Flickr under Creative Commons.)

In other words, YOU and I are the “safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society” in which we live. Our government is not, because everyone can point to one or another excess of the government in which it abused its power and curtailed citizens’ liberties. As individuals, we have much less power and inclination to interfere in the lives of our fellow citizens; our government, on the other hand, seems to have little better to do than to interfere in all our lives.

For us to exercise our control over the government and the powers we grant to it — “with wholesome discretion,” as Jefferson wrote — we need to educate ourselves. And if we fail to do so, and allow the government to abuse its power further and so erode ours, then we have ourselves to blame.

Enjoy the debate!

___

P.S. If anyone is interested, I’ll try to compile a post or two about how I would answer tonight’s debate questions.